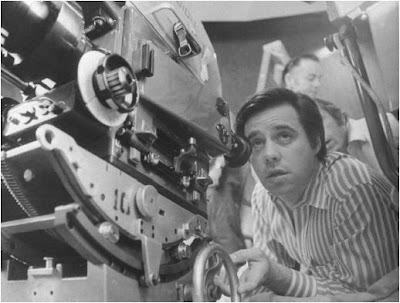

Director Peter Bogdanovich.

Director Peter Bogdanovich.Interviewing Peter Bogdanovich for the April 2002 issue of Venice Magazine was a thrill for me. Like Francis Coppola, John Frankenheimer, and William Friedkin before him, Bogdanovich was one of those filmmakers whose one-sheets hung on my bedroom walls growing up. Plus the fact that he himself had a renowned career as a film historian and interviewer of his own childhood heroes, such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Orson Welles, and dozens of others, made our talk a real feast.

Not long after the article was printed, I received a letter with a New York City postmark. The note enclosed said simply: “Dear Alex, thanks for doing your homework so well, and thanks for the good vibes. All the best to you of love and luck, Peter Bogdanovich.”

Our chat remains one of my favorites during my 15 year tenure as a film writer. --A.S.

PETER BOGDANOVICH’S YEAR OF THE CAT

By

Alex Simon

Peter Bogdanovich is a Hollywood survivor. Few veterans of the business have reached such high highs and hit such low lows as the man who was born to a Serbian father and a Viennese Jewish mother, July 30, 1939 in Kingston, New York. Raised in New York City, Bogdanovich was a precocious child, showing an early affinity for performing and a love of the arts, particularly film. He studied with acting guru Stella Adler in his teens and was acting on stage, as well as directing theater, by his early 20s. Bogdanovich was primarily an actor in his early years, and not a critic, as many people believed due to erroneous reporting and word-of-mouth.

Deciding that making films was where his true passion lay, Bogdanovich came west in the mid-60s, where he quickly forged friendships with some of Hollywood’s most revered veterans: Orson Welles, John Ford, and Howard Hawks, among others. Bogdanovich sat with many of these men for in-depth interviews, many of which are compiled in his much-beloved book, Who the Devil Made It? (which was followed by a compendium of his actor interviews, Who the Hell’s In It?, in 2004). He was able to cut his filmmaking teeth working for B-movie legend Roger Corman on such classic trash as The Wild Angels (1967), which led to his directing debut, the thriller Targets (1968), about a mad sniper and an aging horror film star (Boris Karloff, in one his last, and greatest, turns) whose synchronous paths eventually cross. A low budget gem, the film brought Bogdanovich to the attention of producers Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson, whose BBS Films was the DreamWorks of the late 60s/early 70s. They asked Bogdanovich what he wanted to do next, and the young director told them of this little-known novel about small town Texas in the 1950s…

The Last Picture Show (1971) is widely regarded as one of the seminal films of the 70s, if not the century. A bittersweet coming-of-age film, Picture Show garnered eight Oscar nominations, winning two, for Supporting Actor (Ben Johnson) and Actress (Cloris Leachman), and helped launch a new generation of stars: Jeff Bridges, Cybill Shepherd, Timothy Bottoms, Randy Quaid, Ellen Burstyn, and, especially, Bogdanovich himself, who garnered almost as much press for his affair with Shepherd and the dissolution of his marriage to writer/producer Polly Platt during the film’s production, as he did for the film itself. Bogdanovich had truly arrived. He and Shepherd moved into a palatial estate in Bel-Air. He was an occasional guest host on “The Tonight Show,” and contributor to such high-profile magazines as Esquire and Playboy. Two more cinematic triumphs followed: the zany comedy What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and the charming Paper Moon (1973). He formed a production company with pals and fellow wunderkinds Francis Coppola and William Friedkin, called The Directors Company. It seemed the sky was the limit.

In the mid-70s, Bogdanovich’s fortunes started to shift slightly, starting with a string of box office and critical flops: the period piece Daisy Miller (1974), the musical At Long Last Love (1975), and the comedic look at the early days of moviemaking, Nickelodeon (1976). By 1978, his relationship with Shepherd was over, but he did score a modest critical success with the fine Saint Jack, a low-key gem starring Ben Gazarra as a Vietnam-era American pimp in Singapore.

In 1980 Bogdanovich began his descent into personal and professional hell. While shooting his most personal film, the delightful They All Laughed, he fell in love with actress Dorothy Stratten, 1980’s Playboy Playmate of the Year. Two weeks after the film wrapped, Stratten’s estranged husband murdered the young starlet, and then himself, events later dramatized in Bob Fosse’s final film, Star 80 (1984). It was a horrific end to not only a young woman’s life, but a budding talent that both critics and her co-stars agreed would have developed into something special. Bogdanovich retreated from moviemaking and the public eye for the next four years, writing the controversial book The Killing of the Unicorn, detailing his love for Stratten and the still-reverberating effect her death had on him, and all those who knew her. By the time he did Mask, a critical and box office success in 1985, Bogdanovich was bankrupt, having spent his fortune trying to distribute They All Laughed on his own. He also unsuccessfully sued Universal Pictures for tampering with Mask’s final cut.

The next decade and a half saw a string of attempted come-backs by the once red-hot director, but nothing seemed to take hold, in spite of some solid television work, and a poorly-received sequel to Picture Show entitled Texasville (1990), which was hacked to pieces by its studio, removing nearly 25 minutes of key footage. Bogdanovich's restored cut is available on Pioneer laserdisc.

In spite of these myriad setbacks, Bogdanovich stayed in the ring and kept swinging. He’s scored a knock-out punch with his latest effort, The Cat’s Meow, fascinating piece of historical conjecture, detailing what might have happened on newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst’s yacht in November, 1924, when a disparate group that included Charlie Chaplin, Marion Davies, Louella Parsons, and movie mogul Thomas Ince went for a relaxing getaway to Catalina, only to have one of the passengers mysteriously wind up dead…The film is part Hitchcock, part drawing room comedy, and a pure joy to behold. Fine work across the board from Kirsten Dunst (in her first adult role) as Davies, Edward Hermann as Hearst, Eddie Izzard as Chaplin, and Cary Elwes as Ince. The Lions Gate release hits theaters on April 10th.

Peter Bogdanovich sat down recently to reflect on his remarkable life, openly discussing all its triumphs, tragedies and quirks of fate.

When I heard you were making this film, I was thrilled. I’ve wanted to see this story filmed since reading Hollywood Babylon as a kid.

Peter Bogdanovich: Well, I read about it in Hollywood Babylon, as well, but the person who first told me about it was Orson Welles, about 30 years ago, when I interviewed him for a book we did (This is Orson Welles). The story didn’t make it into the book, but there is a reference to it, which Orson referred to as “a notorious incident.” At the time we did the book, we still couldn’t get into it, if you know what I mean. But 30 years later, the script came to me, and I said ‘My God, it’s that story Orson told me!”

Bogdanovich, in white hat, on the set of The Cat's Meow.

Bogdanovich, in white hat, on the set of The Cat's Meow.Even though the story is based on conjecture, since no one really knows what happened on Hearst’s yacht that night, the events in the film, as they’re portrayed, are pretty much the way most people believe things went down, right? I mean, I don’t think anyone who knows the story today believes that Thomas Ince died of “gastrointestinal distress.”

No, no. And I don’t think they did then, either. The famous quote from D.W. Griffith was “Anytime anyone mentions Tom Ince around Hearst, he turns white. There’s somethin’ funny there.” (laughs) But (the story) feels right. The death haunted everyone who was on that ship.

Well, why else would someone like Louella Parsons have had the career, and the amount of power, that she had? It all started right after Ince died.

That’s certainly a strong argument. She was a real pain in the neck to a lot of people.

Thomas Ince.

Thomas Ince.I’m glad to see that Thomas Ince is being brought back into the public consciousness because, aside from Ince Boulevard in Culver City, he’s largely a forgotten figure, and he was a real pioneer filmmaker.

Well, he wasn’t a poet like Griffith was, but he was a real pioneer in terms of how films are made, particularly the Western, and he was the first person to really come up with the process of doing a lot of pictures at once, which we bring up in the film. He was very ahead of time with the assembly line idea of making pictures.

Ince’s death was almost symbolic, wasn’t it, of a shift in how movies were made and studios were run?

Very true. Coincidentally that year, 1924, was the year (director) Ernst Lubitsch came to Hollywood, which really changed movies forever. He brought Europe to Hollywood in a way that hadn’t happened yet. I asked Jean Renoir once what he thought of Lubitsch. Renoir said “Lubitsch? He invented the modern Hollywood.” Of course, this was during the 60s, and the Hollywood of today is nothing like the Hollywood of that period. So what he really meant was films done from about 1925-1960.

You assembled an incredible cast for this, starting with Edward Hermann, who’s a brilliant choice for Hearst.

We got lucky. He wasn’t the first choice initially, and then he wasn’t available. We were very close to shooting and we didn’t have a Hearst yet. The actor we had cast backed out at the last minute, saying he was exhausted. Finally, it was suggested “What about Ed Hermann?” who I always thought would be great in the part. So it was fortuitous, really. A lot of luck.

There is a Movie God, isn’t there?

Yes, and sometimes He’s against you! (laughs) But sometimes the Gods are on your side. John Ford said to me once, “Most of the good things in pictures happen by accident.” I was shocked by that, at that point having only made one picture. But now I believe it to be very true. Luck is either on your side, or it’s not. (laughs)

It was terrific to see Kirsten Dunst playing an adult. She gave the part a lot of depth. The other portrayals of Marion Davies I’ve seen have been pretty cartoonish.

She was wonderful, wasn’t she? She worked really hard at it, and always wanted to do a 20s story. She has a wonderful period face, looks great in those clothes, and has great instincts.

L to R: Edward Hermann as William Randolph Hearst, Kirsten Dunst as Marion Davies, Eddie Izzard as Charlie Chaplin and Jennifer Tilly as Louella Parsons, in The Cat's Meow.

L to R: Edward Hermann as William Randolph Hearst, Kirsten Dunst as Marion Davies, Eddie Izzard as Charlie Chaplin and Jennifer Tilly as Louella Parsons, in The Cat's Meow.Eddie Izzard, who plays Charlie Chaplin, was terrific also. I wasn’t that familiar with him, prior to this film.

Well, Eddie’s a very famous British comedian. He’s not a standup in the traditional sense. He’s more like Richard Pryor was: he acts the comedy. He got two Emmys for the HBO special he did a couple years ago. Again, luck. My manager was handling him for a while and suggested that I see his act. So I went and saw his act, and he was hilarious. And while I was watching him being hilarious, acting this comedy, it suddenly hit me that he’d be perfect for Chaplin, because that was the toughest part to cast. He doesn’t look like Charlie, but the idea of an English comedian playing an English comedian wasn’t too much of a stretch. It turned out that he loved Chaplin, and also loved the idea that Chaplin wasn’t funny in this. He wanted to play a dramatic role.

From everything I’ve heard, in real life Chaplin was as serious as a heart attack.

Yeah, he was pretty serious. I met him once, late in his life, when he came out for the Oscars in ’72. He was having problems with his memory at the time, but was still madly in love with his wife, Oona. He was a little frail, and not particularly funny. You know how I met him? He was given a special Academy Award that year and my film, The Last Picture Show, was nominated for several awards. Coincidentally, the producer of The Last Picture Show, Bert Schneider, had made a deal with the owner of the Chaplin film library to bring all of Charlie’s old movies out again. Bert knew that I knew a lot about old pictures and asked if I would cut together a bunch of clips for the tribute before the award was given to Chaplin. He asked me what I needed, and I gave him a list of the pictures and an editor to work with. The compilation of clips I put together was 13 ½ minutes long, with the final 4 minutes being from The Kid (1921). I get a call from Bert later: “The Academy said it’s too long. We can’t run it. What do you want to do?” I said, “Bert, it’s Charlie Chaplin!” Bert agreed and called the Academy back, saying “We won’t cut it. It’s Charlie Chaplin, for God’s sake!” The Academy said “We won’t run a 13 ½ minute film clip on a live broadcast!” Bert said “Okay, then Charlie won’t come to the ceremony!” They ran it. (laughs)

Yeah, I’d say that was a deal-breaker.

(both laugh) It was marvelous. Everyone was crying at the end of it.

Your book, Who the Devil Made It?, is a terrific collection of the interviews you’ve done with classic filmmakers, from people like silent film pioneer Allan Dwan (who helmed the 1922 version of Robin Hood, with Douglas Fairbanks), to Sidney Lumet (Serpico, 1973), who got his start in live TV.

Thank you. I’m actually working on a sequel, called Who the Hell’s In It?, which is a collection of pieces on actors. There’s profiles of John Wayne, Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, Marlene Deitrich…It’s a different kind of book than the first one. It’s not all Q & A like the first book, although there is some. The first chapter is about Lillian Gish, and the second is about Bogart, who I never met. It’s got some of the magazine articles that I’ve written over the years. There’s a brief chapter on Marilyn Monroe also, who I never really met, although I saw her once in an acting class of Lee Strasberg’s that I audited, in New York.

Bogdanovich's collection of director interviews (above) and actor interviews (below), both best-sellers.

Bogdanovich's collection of director interviews (above) and actor interviews (below), both best-sellers.

Let’s talk about your background. You grew up in New York. Your father was a Serb, and your mother a Viennese Jew.

Mom was Jewish and dad was Serbian-Greek Orthodox, although we had no religious training at all. My parents were turned off by orthodox religions.

For your early youth, you were essentially an only child.

Yeah, my younger sister was born when I was 13.

Bogdanovich sits with Orson Welles on the set of Mike Nichols' Catch-22, being photographed by Candice Bergen, 1969.

Bogdanovich sits with Orson Welles on the set of Mike Nichols' Catch-22, being photographed by Candice Bergen, 1969.It sounds like it was your dad who really introduced you to the movies.

They took me to see regular pictures like Dumbo (1941), which was the first picture I ever saw, and I had to be taken out of the theater, screaming! (laughs) But my first really exciting experience at any kind of theater was at the opera, at the old Metropolitan Opera House. It was “Don Giovanni.” I remember him going to Hell at the end. It scared the shit out of me! (laughs) Then I started going with my dad to the Museum of Modern Art, where we saw silent movies, which is where I first saw Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Laurel & Hardy. I loved silent movies, actually, and it’s a good thing that I did, because it’s the foundation of movies. I think we’ve kind of lost contact with that.

Was there one film you saw during that period that did it for you, where you said “This is what I have to do”?

Well, I always loved the movies, but originally thought I was going to be an actor. When I was ten years old, my three favorite movies were Red River (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and The Ghost Goes West (1936), which was written by Robert E. Sherwood, produced by Alexander Korda, directed by Rene Clair, and starred Robert Donat. I must’ve seen that picture six or seven times. I just loved it, my favorite of the three. In fact, I’ve been planning a ghost picture. I’ve been planning one for 20 years. Mine’s called Wait for Me. I’m sure it all goes back to The Ghost Goes West.

Stella Adler was your primary acting teacher. Tell us about her.

She was a great woman, larger than life, very theatrical, very funny. She was extraordinarily influential on me, and a number of other people. Marlon Brando said that she taught him everything he knows. She influenced acting in movies to such a degree that she changed acting, as did Brando. She was just an extraordinary woman. I learned so much about the art of the theater and art in general. Stella didn’t think that art of any kind should be small. She thought it should be bigger than the kitchen sink, and should speak to important subjects.

John Huston, Orson Welles, and Bogdanovich, early '70s.

John Huston, Orson Welles, and Bogdanovich, early '70s.Was Orson Welles sort of a second father to you?

It’s funny, several people have commented that I’ve had several different fathers in my life. Orson filled in an awful lot of things that my father wasn’t equipped to do. My father was equipped to do a lot of things, but emotionally…he’d had a tough life. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to spend as much time with my father as I’d have liked. He died when I was quite young, while I was shooting Picture Show, in fact. Orson was more like an older brother, in many ways. He was a great authority figure, but he was still very boyish. It’s funny, Orson always wanted a son, but had all these daughters instead. He always said, “I don’t know what to do with women.” (laughs)

The first thing you directed was in New York on the stage, right?

Yeah, in 1959. I was 20. My first claim to fame was introducing Carroll O’Connor in the production. From there, he got an agent, went to Hollywood, and the rest is history. He gave me credit for that, once. When he won his first Golden Globe, for “All in the Family,” I was nominated for Picture Show. I was sitting down by the winner’s podium and he said “There’s a young director who’s nominated here tonight who gave me my start in New York. He’s an arrogant son of a bitch, but I thank him.” (laughs)

When you realized you wanted to direct films instead of plays, you came to Hollywood. It was then that you met all these amazing directors of yesteryear, whom you interviewed. Since you didn’t go to college, was this your film school, so to speak?

Absolutely. You put it in a nutshell. It was like the greatest university, or master’s class that one could get. I was able to put myself through this with all these pioneers who were still alive then. Independent film wasn’t really around at that point and the only ting going on in New York was the underground movement, with Andy Warhol and that crowd. That wasn’t my thing. One of the main reasons I came out to Hollywood was to meet and learn from these old masters. How do you get to know about this medium unless you ask the people who’ve done it? And they were all here: Jack Ford, Howard Hawks, King Vidor. There’s a lot of people I talked to who I didn’t officially interview. But I was able to actually sit and interview 18 of these directors.

Bogdanovich interviews Jimmy Stewart, late 1960s.

Bogdanovich interviews Jimmy Stewart, late 1960s.Stylistically, the two directors who’ve influenced you the most are John Ford and Howard Hawks.

I guess that’s true, although you’d also have to include Orson Welles, not stylistically, but in other ways.

If I were someone off the street, with just a layman’s knowledge of movies, and I asked you to tell me the difference between the films of Hawks and Ford, what would you tell me?

I asked Orson that question once, and he gave me the best answer. He said “At their best, Hawks is great prose, but Ford is poetry.” I think he was right. That’s accurate. Although Ford made more pictures that don’t work today, than Hawks did. Ford’s films had a sentimentality that Hawks’ didn’t.

Director John Ford.

Director John Ford.What’s your favorite Ford picture?

It varies. I love The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1957), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Also My Darling Clementine (1946), They Were Expendable (1945). These were all great pictures.

Director Howard Hawks.

Director Howard Hawks.What about your favorite Hawks film?

To Have and Have Not (1944), Rio Bravo (1959), The Big Sleep (1946), Bringing Up Baby (1939), Twentieth Century (1934).

It’s amazing that one man made all those movies, all from different genres.

I know. He was remarkable.

I think Scarface (1932) still holds up really well. It was one of the first films cut for action, wasn’t it? The editing still feels very contemporary.

Yeah, it’s just superb on every level, except for that horrible post-script that was slapped on the end of it, with these newspaper men standing around, pontificating about what a horrible thing we’d just witnessed. And what really irks me about Red River, which is one of my favorites, is that you can’t see the right version anymore. The version they have on video, which is listed as the “Director’s Cut,” is not! I’ve tried to call the people who own the rights and tell them, ‘Not only is this not the “Director’s Cut,” it’s the cut that Howard disowned!’

How are the two cuts different?

There’s the narrated version, and the text version, where there’s this big book where the pages keep turning. That was the preview version which Hawks threw out, and rightfully so. It’s too slow. Then he had the version that Walter Brennan narrated. That’s the version that Howard liked, but you can’t see it anymore. Maybe they can’t find the other cut, which would be tragic.

Let’s talk about your time with Roger Corman.

Previous to my work on The Wild Angels, Roger had asked me to write a script for him a war script, something that he could shoot in Poland, where he had a great location scouted out. “Sort of like Bridge on the River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia, but cheap!” (laughs) And that was the beginning of a script called The Criminals, which never got made, but was a pretty good script. Then I got the call from Roger to work as his assistant on The Wild Angels, which was then called All the Fallen Angels. That was an incredible experience. Twenty-two weeks I worked on that. I directed 2nd unit and cut my own footage. I also re-wrote the entire script, but didn’t get credit. To this day, I don’t think even Peter Fonda knows I wrote that picture. (laughs) I learned a lot. Roger throws you in the water and says “Swim!”

Bogdanovich's directing debut, Targets (1968).

Bogdanovich's directing debut, Targets (1968).All of this led to a terrific film, called Targets.

Thank you, and unfortunately, it’s still relevant. We based it on Charles Whitman’s shooting spree at University of Texas in 1966. My first wife (Polly Platt) and I collaborated on the story. I wrote the first draft of the script, then Samuel Fuller (The Steel Helmet, 1951; Shock Corridor, 1963) asked to read it, and during about two hours of conversation, he re-wrote the entire script! Sammy wouldn’t take credit for his work. He said “No credit, kid! If you give me credit, they’ll think I did everything!” And he practically did! He was a great guy. Boris Karloff owed Roger two days work on a picture, so that’s how Karloff became involved, and we interwove the parallel stories of this aging horror film star and this homicidal maniac until their paths eventually crossed.

Director Sam Fuller.

Director Sam Fuller.Was your character in the film, Sammy, named after Samuel Fuller?

Right, “Sammy Michaels,” Michael being Sam’s middle name. I owe a lot to Sammy. The film got some good reviews and some attention, and that’s really what got me Picture Show.

Bogdanovich with Boris Karloff in Targets (1968).

Bogdanovich with Boris Karloff in Targets (1968).What was Mr. Karloff like?

Oh, what a wonderful man he was. He was just sweet and dear, and very funny, very acerbic. He was 79 when we shot that, and very ill at the time. But he never complained. He was a real trooper, especially when we shot the drive-in stuff. We only had him for one day during that sequence!

Let’s talk about Picture Show. Sal Mineo gave me the book originally, and had always wanted to play the part of Sonny (played in the film by Timothy Bottoms). By then, he was too old, but he thought I’d like it, and I did. I didn’t really know how to make it initially, until I realized the only way to make it was just to make it! (laughs) To shoot the book, which is basically what we did: we just shot the book. The script followed Larry McMurtry’s original construction which was basically one football season to the next in this small town. How were you able to make the film relevant to yourself since, here you were, a New Yorker, making a picture about kids in small town Texas during the early 50s? I think the teenage experience is similar everywhere, which is why people who saw the picture and grew up in places like New York, or Europe, or Australia, all related to it very deeply. That’s why it has universality. It did for me, even though Texas for me was a foreign country. I approached it like a foreign country, learning about the music, watching the people, how they dressed, how they interacted. I never even knew who the hell Hank Williams was before that picture! (laughs)

Jeff Bridges and Cybill Shepherd in The Last Picture Show (1971). Do you feel that Picture Show on one hand was a terrific experience because it made your career, but on the other hand, that it’s also become your cross to bear? No, I don’t. I mean, unlike Orson, who did feel that way about Citizen Kane, I don’t feel that way because I have made other pictures that did business and that people liked, whereas with Orson, it was the only one that people had ever heard of. He made great films that no one’s ever heard of. When people approach me, they don’t just mention Picture Show, there are other films they’ve liked, but that wasn’t the case with Orson. In fact, he said to me once—we were talking about Greta Garbo, and he loved Garbo—I said, ‘Isn’t it a pity with all the movies she made, she did only two really great ones.’ Orson says “Well, you only need one.” (laughs) So I thought, if you only need one, at least I got the one out of the way early on. What’s Up, Doc? is another terrific film. It’s been said by critics and film scholars that Picture Show was your John Ford homage and Doc was your Howard Hawks homage. (groans) Oh God, they always say that shit. I think all that started because I had to open my big mouth, and I said something to the effect that The Last Picture Show was inspired by The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942) because they’re both about the end of an era. From there on it went because there were some obvious John Fordian moments with a couple of the long shots and shots of the sky. All of my reviews in the 70s and 80s were predicated on a basic piece of misinformation, which is that I began as a critic. So all the reviews were “Well, he was a critic, so this is his ‘X’ movie and this is his ‘Y’ movie,” which is bullshit! I was never a critic. I was an actor!

Jeff Bridges and Cybill Shepherd in The Last Picture Show (1971). Do you feel that Picture Show on one hand was a terrific experience because it made your career, but on the other hand, that it’s also become your cross to bear? No, I don’t. I mean, unlike Orson, who did feel that way about Citizen Kane, I don’t feel that way because I have made other pictures that did business and that people liked, whereas with Orson, it was the only one that people had ever heard of. He made great films that no one’s ever heard of. When people approach me, they don’t just mention Picture Show, there are other films they’ve liked, but that wasn’t the case with Orson. In fact, he said to me once—we were talking about Greta Garbo, and he loved Garbo—I said, ‘Isn’t it a pity with all the movies she made, she did only two really great ones.’ Orson says “Well, you only need one.” (laughs) So I thought, if you only need one, at least I got the one out of the way early on. What’s Up, Doc? is another terrific film. It’s been said by critics and film scholars that Picture Show was your John Ford homage and Doc was your Howard Hawks homage. (groans) Oh God, they always say that shit. I think all that started because I had to open my big mouth, and I said something to the effect that The Last Picture Show was inspired by The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942) because they’re both about the end of an era. From there on it went because there were some obvious John Fordian moments with a couple of the long shots and shots of the sky. All of my reviews in the 70s and 80s were predicated on a basic piece of misinformation, which is that I began as a critic. So all the reviews were “Well, he was a critic, so this is his ‘X’ movie and this is his ‘Y’ movie,” which is bullshit! I was never a critic. I was an actor!  Bogdanovich lines up a shot on the set of What's Up Doc? (1972) They were trying to make you into the American Francois Truffaut. Right, exactly. I had written about film, but I was a popularizer more than anything. I wrote features and interviewed people who interested me. But to say that I consciously thought this picture was an homage to someone was ridiculous! They even said that Paper Moon was my homage to Shirley Temple! Give me a break! (laughs) Did you ever see Shirley Temple light up a Lucky Strike or swear? It was anti-Shirley Temple! So it was completely wrong and it went on for years. With What’s Up, Doc? we had a similar set-up to Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby (1938), which was “daffy dame meets stuffy professor,” plus one joke, where she rips his jacket, but that’s it. The challenge on that picture was “How do you do a picture with Barbara Streisand?” Well, you make a screwball comedy. She actually wanted to do a drama because she’d just done a comedy (The Owl and the Pussycat, 1970), but I’d just done a drama, so I wanted to do a comedy. (laughs) In the end, I won. It was really a picture that was almost made on a dare. I had more fun on that picture than anything I’ve ever done.

Bogdanovich lines up a shot on the set of What's Up Doc? (1972) They were trying to make you into the American Francois Truffaut. Right, exactly. I had written about film, but I was a popularizer more than anything. I wrote features and interviewed people who interested me. But to say that I consciously thought this picture was an homage to someone was ridiculous! They even said that Paper Moon was my homage to Shirley Temple! Give me a break! (laughs) Did you ever see Shirley Temple light up a Lucky Strike or swear? It was anti-Shirley Temple! So it was completely wrong and it went on for years. With What’s Up, Doc? we had a similar set-up to Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby (1938), which was “daffy dame meets stuffy professor,” plus one joke, where she rips his jacket, but that’s it. The challenge on that picture was “How do you do a picture with Barbara Streisand?” Well, you make a screwball comedy. She actually wanted to do a drama because she’d just done a comedy (The Owl and the Pussycat, 1970), but I’d just done a drama, so I wanted to do a comedy. (laughs) In the end, I won. It was really a picture that was almost made on a dare. I had more fun on that picture than anything I’ve ever done.  Ryan and Tatum O'Neal in Paper Moon (1973). Paper Moon recreates a time and place better than any film I’ve ever seen. We worked really hard to get that period-feel right. We shot all over Kansas and a few weeks in Missouri. I think it’s the best work Ryan O’Neal’s done. That wonderful laugh he came up with, that cackle, was just wonderful. Paramount owned the property originally and had John Huston lined up to direct with Paul Newman and his daughter to star. Then they wanted me to direct, but I didn’t particularly want to do it with Paul. I wanted to do it with Ryan, so that’s what happened. Around this time, you, William Friedkin, and Francis Coppola formed The Directors Company, which seemed like a great idea. What happened? I thought it was a great idea and made two pictures for the company (Paper Moon and Daisy Miller). Francis made one (The Conversation, 1973), and Billy never did a picture for the company, then decided he didn’t want to make any pictures for the company. He wanted to make more money. The money we could make was limited to a certain amount, which I thought was perfectly good, but Friedkin felt he wanted more money, and more money for the budget. Our deal was, we could make any picture we wanted, as long as it was three million or under, which was a lot of money in those days. We could also produce a movie for someone else if it wasn’t more than $1.5 million. We didn’t’ even have to show them a script! It was a great deal, and I wish I could get one like it again. That kind of freedom is worth gold, I think. It was a shame. What did you think of Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders and Raging Bulls, the notorious account of this period in Hollywood? I dipped into about three pages of it in a book shop and got nauseous. (Biskind) just didn’t get it at all. He’d interviewed me a couple times and quoted people who either weren’t around or didn’t know what they were talking about. It was just awful. A bad book from a very good writer.

Ryan and Tatum O'Neal in Paper Moon (1973). Paper Moon recreates a time and place better than any film I’ve ever seen. We worked really hard to get that period-feel right. We shot all over Kansas and a few weeks in Missouri. I think it’s the best work Ryan O’Neal’s done. That wonderful laugh he came up with, that cackle, was just wonderful. Paramount owned the property originally and had John Huston lined up to direct with Paul Newman and his daughter to star. Then they wanted me to direct, but I didn’t particularly want to do it with Paul. I wanted to do it with Ryan, so that’s what happened. Around this time, you, William Friedkin, and Francis Coppola formed The Directors Company, which seemed like a great idea. What happened? I thought it was a great idea and made two pictures for the company (Paper Moon and Daisy Miller). Francis made one (The Conversation, 1973), and Billy never did a picture for the company, then decided he didn’t want to make any pictures for the company. He wanted to make more money. The money we could make was limited to a certain amount, which I thought was perfectly good, but Friedkin felt he wanted more money, and more money for the budget. Our deal was, we could make any picture we wanted, as long as it was three million or under, which was a lot of money in those days. We could also produce a movie for someone else if it wasn’t more than $1.5 million. We didn’t’ even have to show them a script! It was a great deal, and I wish I could get one like it again. That kind of freedom is worth gold, I think. It was a shame. What did you think of Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders and Raging Bulls, the notorious account of this period in Hollywood? I dipped into about three pages of it in a book shop and got nauseous. (Biskind) just didn’t get it at all. He’d interviewed me a couple times and quoted people who either weren’t around or didn’t know what they were talking about. It was just awful. A bad book from a very good writer.  Daisy Miller and At Long Last Love, Bogdanovich's first two flops.

Daisy Miller and At Long Last Love, Bogdanovich's first two flops.  Nickelodeon was an interesting film. Well, I’m not completely happy with the way that picture turned out. Both Nickelodeon and At Long Last Love were sort pet projects of mine and neither came out the way I wanted, which is the reason I stopped making pictures for three years. I mean, they were okay, but they just didn’t turn out right. Nickelodeon was meant to be in black & white and I wanted John Ritter and Cybill and Jeff Bridges and…I just had a smaller picture in mind. Both Burt Reynolds and Ryan (O’Neal) were good in it, and Jane Hitchcock was good, but she didn’t have any threat about her. So I quit making pictures for a while, because I felt both films had been compromised. Somehow, I’d had all this success then suddenly made these pictures that I felt were compromised. So I went back to basics and made my next two pictures exactly the way I wanted, but for less money. People thought I couldn’t get a job during that period, which is absolute nonsense.

Nickelodeon was an interesting film. Well, I’m not completely happy with the way that picture turned out. Both Nickelodeon and At Long Last Love were sort pet projects of mine and neither came out the way I wanted, which is the reason I stopped making pictures for three years. I mean, they were okay, but they just didn’t turn out right. Nickelodeon was meant to be in black & white and I wanted John Ritter and Cybill and Jeff Bridges and…I just had a smaller picture in mind. Both Burt Reynolds and Ryan (O’Neal) were good in it, and Jane Hitchcock was good, but she didn’t have any threat about her. So I quit making pictures for a while, because I felt both films had been compromised. Somehow, I’d had all this success then suddenly made these pictures that I felt were compromised. So I went back to basics and made my next two pictures exactly the way I wanted, but for less money. People thought I couldn’t get a job during that period, which is absolute nonsense.  Bogdanovich with Ryan O'Neal and Burt Reynolds on the set of Nickelodeon (1976), another personal and critical disappointment. What did you do during that period? I went around the world with Cybill twice, and turned down a lot of pictures. I didn’t want to work again until I figured out how I could work with integrity. So after that, I did Saint Jack, which turned out well and was an amazing experience, and then They All Laughed, which is my own favorite, but became a tragedy when Dorothy (Stratten) was murdered. That’s something that we’ve never gotten over, but we’ve all had to move on from. I say “we” meaning the people who were close to her.

Bogdanovich with Ryan O'Neal and Burt Reynolds on the set of Nickelodeon (1976), another personal and critical disappointment. What did you do during that period? I went around the world with Cybill twice, and turned down a lot of pictures. I didn’t want to work again until I figured out how I could work with integrity. So after that, I did Saint Jack, which turned out well and was an amazing experience, and then They All Laughed, which is my own favorite, but became a tragedy when Dorothy (Stratten) was murdered. That’s something that we’ve never gotten over, but we’ve all had to move on from. I say “we” meaning the people who were close to her.  Bogdanovich with cinematographer Robby Muller, Monika Subramaniam, and Ben Gazzara on the Singapore set of Saint Jack (1978). What was it like shooting Saint Jack on location in Singapore? Well, it was…fascinating. (laughs) One of the most life-altering experiences I’ve ever been through. It was comparable in my life to the upheaval of my personal life during Picture Show. My relationship with Cybill technically ended with that. I was gone for six months and Ben Gazzara was there for four months. We only shot 12 weeks, but the rest of the time was spent doing a lot of research and preparation. We had a bare bones script but no real characters and no women at all. It was a story about a pimp and his hookers, and we had no women characters! So, to be candid, I didn’t know that much about hookers and the writer, Paul Theroux, wasn't much help, so Benny and I and all of us got pretty involved in the scene there. It was pretty extraordinary, what we learned, about all of these women and how they came to be there, and basically much of what’s in the film was based on what we learned from these real hookers. Singapore is sort of the melting pot of Asia, like New York is for the U.S. All those locations you saw were real, most of which are gone now, and most of the cast were non-professionals.

Bogdanovich with cinematographer Robby Muller, Monika Subramaniam, and Ben Gazzara on the Singapore set of Saint Jack (1978). What was it like shooting Saint Jack on location in Singapore? Well, it was…fascinating. (laughs) One of the most life-altering experiences I’ve ever been through. It was comparable in my life to the upheaval of my personal life during Picture Show. My relationship with Cybill technically ended with that. I was gone for six months and Ben Gazzara was there for four months. We only shot 12 weeks, but the rest of the time was spent doing a lot of research and preparation. We had a bare bones script but no real characters and no women at all. It was a story about a pimp and his hookers, and we had no women characters! So, to be candid, I didn’t know that much about hookers and the writer, Paul Theroux, wasn't much help, so Benny and I and all of us got pretty involved in the scene there. It was pretty extraordinary, what we learned, about all of these women and how they came to be there, and basically much of what’s in the film was based on what we learned from these real hookers. Singapore is sort of the melting pot of Asia, like New York is for the U.S. All those locations you saw were real, most of which are gone now, and most of the cast were non-professionals.  Bogdanovich and the late Dorothy Stratten on the set of They All Laughed. They All Laughed is one of my favorite of your films. It certainly is mine. It was a labor of love. Everyone in it was either in love, falling in love, falling out of love, or having problems with love. In that film, like in Saint Jack, we inferred a lot, instead of spelling it all out, which some people took as meaning it had nothing to say. Unfortunately, tragically, Dorothy Stratten was murdered two weeks after we wrapped, so nobody from that moment on could ever see her or the movie as we intended it. It was intended to be bittersweet. The sweet was supposed to be Dorothy and John Ritter. The bitter was supposed to be Audrey Hepburn and Ben Gazzara. But after Dorothy’s death, it was all bitter.

Bogdanovich and the late Dorothy Stratten on the set of They All Laughed. They All Laughed is one of my favorite of your films. It certainly is mine. It was a labor of love. Everyone in it was either in love, falling in love, falling out of love, or having problems with love. In that film, like in Saint Jack, we inferred a lot, instead of spelling it all out, which some people took as meaning it had nothing to say. Unfortunately, tragically, Dorothy Stratten was murdered two weeks after we wrapped, so nobody from that moment on could ever see her or the movie as we intended it. It was intended to be bittersweet. The sweet was supposed to be Dorothy and John Ritter. The bitter was supposed to be Audrey Hepburn and Ben Gazzara. But after Dorothy’s death, it was all bitter.  Ben Gazzara and Audrey Hepburn in They All Laughed. Tell us about Audrey Hepburn. She was so magical. She broke your heart. Audrey was everything anybody thought she was: she had grace under pressure; she was a complete professional without one egoesque moment in her life; she cared about people; she had a great sense of humor; she was quietly sexy in a very ladylike way; she was very girlish, still at age 50. It was her last starring picture, which I knew it would be, strangely enough. She just wasn’t that into (acting) anymore. I think she preferred bringing up her children…I always felt that picture would never really work until everyone in the picture was dead, and then it would sort of become neutral again. With Dorothy and Audrey now gone, I think it’s taken on a little distance. A lot of audiences, like in Seattle and Beverly Hills, really liked it and got it, but I never should have tried to distribute the picture myself.

Ben Gazzara and Audrey Hepburn in They All Laughed. Tell us about Audrey Hepburn. She was so magical. She broke your heart. Audrey was everything anybody thought she was: she had grace under pressure; she was a complete professional without one egoesque moment in her life; she cared about people; she had a great sense of humor; she was quietly sexy in a very ladylike way; she was very girlish, still at age 50. It was her last starring picture, which I knew it would be, strangely enough. She just wasn’t that into (acting) anymore. I think she preferred bringing up her children…I always felt that picture would never really work until everyone in the picture was dead, and then it would sort of become neutral again. With Dorothy and Audrey now gone, I think it’s taken on a little distance. A lot of audiences, like in Seattle and Beverly Hills, really liked it and got it, but I never should have tried to distribute the picture myself.  The cast of They All Laughed poses in front of the film's poster. Why did you buy the rights to the film and then try to distribute it yourself after Dorothy’s death? Because I was out of my mind. It was a disaster. I was an idiot. I was so paranoid after Dorothy’s murder, I wanted to protect the picture at all costs and was afraid they would fuck up the distribution. I wanted to pull away from the studio that was handling it, and I did, by buying the rights to the picture for $350,000 cash, which at the time was a lot of money, plus the guarantees that wound up costing me $5 million! The point is, it was a mistake brought on by paranoia and grief, and not dealing with the grief, and just trying to write a book about it, thinking that would be enough, but it wasn’t. In writing the book, I thought I was venting all my anger, which I was, but in the end, the only person I ended up hurting was myself. I lost my financial freedom as a result. Nevertheless, I learned a few things, one of which is you cannot, in any event, self-distribute. The only person who ever got away with it was (John) Cassavetes, who very successfully distributed A Woman Under the Influence (1974), but then lost it all over Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976). You just can’t fight these people. By 1985, I was bankrupt. The only reason I got through ’83 is because I did Mask, which I had to do because I was broke.

The cast of They All Laughed poses in front of the film's poster. Why did you buy the rights to the film and then try to distribute it yourself after Dorothy’s death? Because I was out of my mind. It was a disaster. I was an idiot. I was so paranoid after Dorothy’s murder, I wanted to protect the picture at all costs and was afraid they would fuck up the distribution. I wanted to pull away from the studio that was handling it, and I did, by buying the rights to the picture for $350,000 cash, which at the time was a lot of money, plus the guarantees that wound up costing me $5 million! The point is, it was a mistake brought on by paranoia and grief, and not dealing with the grief, and just trying to write a book about it, thinking that would be enough, but it wasn’t. In writing the book, I thought I was venting all my anger, which I was, but in the end, the only person I ended up hurting was myself. I lost my financial freedom as a result. Nevertheless, I learned a few things, one of which is you cannot, in any event, self-distribute. The only person who ever got away with it was (John) Cassavetes, who very successfully distributed A Woman Under the Influence (1974), but then lost it all over Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976). You just can’t fight these people. By 1985, I was bankrupt. The only reason I got through ’83 is because I did Mask, which I had to do because I was broke.  There was a four year gap between They All Laughed and Mask. Yeah. I was consumed with distributing They All Laughed and writing Killing of the Unicorn. I turned down a lot of offers during that time. I just couldn’t do anything. My agent (would say) “Forget it, don’t even ask him. He’s writing a book,” which, of course, got me into even more trouble. It sounds like you did Mask for the money, initially. Initially, yes. The script, which was originally 100 pages that dealt with Rocky Dennis’ life, needed a lot of work. So I sat through nine drafts of that picture working with this writer, working on the construction and the dialogue. Then we shot the picture and I rewrote most of the biker dialogue on the set with Cher and Sam Elliott. I got into it, aside from the money, because it reminded me of how Dorothy was very taken with The Elephant Man. She bought a book that was a serious study of John Merrick, the Elephant Man, and had seen the play on Broadway. I remember her buying it at Doubleday one night and the photographs were rather graphic. I couldn’t look at them, but she was riveted. I figured out later that she identified with him. Here was this gorgeous creature that everyone would stop and stare at, from adults, to kids, to dogs. Just gawk at her. Dogs especially would just go to her like she was a goddamn milkmaid! And she never understood why she had this extraordinary affect. She just radiated this extraordinary beauty and goodness, which the camera never captured. She was too complicated for the camera. Her face changed every few seconds. It was quite amazing. A lot of people who knew her said that. So what made me decide to do Mask, really, was thinking back to Dorothy’s complete lack of ease when people looked at her. She said, “I feel like I have ice cream on my shirt, or something.” There was this connection with Dorothy feeling like an outsider because of her beauty, and Rocky Dennis’ feeling like an outsider because people found him hard to look at. The two are not dissimilar.

There was a four year gap between They All Laughed and Mask. Yeah. I was consumed with distributing They All Laughed and writing Killing of the Unicorn. I turned down a lot of offers during that time. I just couldn’t do anything. My agent (would say) “Forget it, don’t even ask him. He’s writing a book,” which, of course, got me into even more trouble. It sounds like you did Mask for the money, initially. Initially, yes. The script, which was originally 100 pages that dealt with Rocky Dennis’ life, needed a lot of work. So I sat through nine drafts of that picture working with this writer, working on the construction and the dialogue. Then we shot the picture and I rewrote most of the biker dialogue on the set with Cher and Sam Elliott. I got into it, aside from the money, because it reminded me of how Dorothy was very taken with The Elephant Man. She bought a book that was a serious study of John Merrick, the Elephant Man, and had seen the play on Broadway. I remember her buying it at Doubleday one night and the photographs were rather graphic. I couldn’t look at them, but she was riveted. I figured out later that she identified with him. Here was this gorgeous creature that everyone would stop and stare at, from adults, to kids, to dogs. Just gawk at her. Dogs especially would just go to her like she was a goddamn milkmaid! And she never understood why she had this extraordinary affect. She just radiated this extraordinary beauty and goodness, which the camera never captured. She was too complicated for the camera. Her face changed every few seconds. It was quite amazing. A lot of people who knew her said that. So what made me decide to do Mask, really, was thinking back to Dorothy’s complete lack of ease when people looked at her. She said, “I feel like I have ice cream on my shirt, or something.” There was this connection with Dorothy feeling like an outsider because of her beauty, and Rocky Dennis’ feeling like an outsider because people found him hard to look at. The two are not dissimilar.  Eric Stoltz, Cher and Bogdanovich on the Mask set. Making it must’ve been a cathartic experience for you. Yeah, it was, although what you saw up on the screen was only 90% of what we did. We ran afoul of the studio head, who had other interests in mind, and ours was not one of them. They cut about eight minutes of key scenes, and changed the music on the soundtrack. The character of Rocky loved Bruce Springsteen. His whole room was the Beatles and Bruce Springsteen posters, for God’s sake! They didn’t want to make a deal to use Bruce’s music, so they replaced it with Bob Seger, without my approval. There was a deal to be made, too. Bruce wanted his music to be a part of this film. We had an understanding that if it wasn’t going to be Springsteen, it would be the Beatles! But they made a deal with Seger behind my back. And I like Bob Seger’s music very much, so it had nothing to do with the quality of his work, but it just wasn’t right for the picture. So, I filed a lawsuit which, again, I shouldn’t have done. That was a mess. It hurt the picture and it hurt me. After seeing your original cuts of Mask and Texasville, both of which were tampered with by their studios, it’s amazing how different, and how much better, your cuts are. They’re completely different films than what were released. Yeah, they cut 25 minutes out of Texasville, which was supposed to be a bittersweet picture like Picture Show was. They wound up cutting most of the bitter and keeping in the sweet, which completely threw it off balance. And the thing is, when the schmucks in the executive suite do this to your picture, you as the director are the one who gets blamed, not the studio people who ruined it! I did another film called Illegally Yours (1988), with Rob Lowe, that I had high hopes for, but it was re-cut completely by Dino De Laurentiis. It’s not a good picture, and that’s why. I hope we can do DVDs of the original cuts of Mask and Texasville, which actually was available on Pioneer laserdisc, but is now out of print. We’ll see… (Editor’s note: PB's cut of "Mask" is now available on DVD, as is his black & white cut of "Nickelodeon"). Obviously with 25 minutes added, Texasville is a completely different picture, but it amazed me how different Mask was with just an extra eight minutes and Springsteen on the soundtrack, instead of Seger. Yes, it all counts. It all matters. If you tamper with something like that and remove a part of it, the whole structure comes tumbling down, like a house of cards. The people who run the studios don’t realize this because they’re not filmmakers. But this is nothing new. You can go back to the silent days and filmmakers were treated the same way, like Erich Von Stroheim, whose eight-hour epic masterpiece Greed (1925) was cut down to two hours and twenty minutes by its studio. Think that was a different movie? (laughs) The point is, they know what they’re getting into going into it. To green light a picture that’s built a certain way, and then tear it apart once it’s been completed in that way, does this make sense? You’ve probably had more high highs and low lows than anyone I’ve interviewed in the film business. How do you keep hope alive and keep your chin up during those bad times? I don’t know. (long pause) I don’t know…My mother and father, I suppose, set a fairly good foundation for me, so I haven’t sunk into the earth yet. (laughs) I think they had kind of a sense of art and culture and civilization that they instilled in me that helped give me some strength. Then, of course, there’s my family, and in the case of Dorothy, Dorothy’s family as well. So I was never alone in these things. Some sense of the past, I suppose, also helps. Do you think it’s just a matter of knowing who you are? That doesn’t hurt. A lot of people, especially recently, have experienced tragedy on a huge scale. I think you learn to live with it, as opposed to getting over it. As far as movies are concerned, they pale in comparison to a real life tragedy.

Eric Stoltz, Cher and Bogdanovich on the Mask set. Making it must’ve been a cathartic experience for you. Yeah, it was, although what you saw up on the screen was only 90% of what we did. We ran afoul of the studio head, who had other interests in mind, and ours was not one of them. They cut about eight minutes of key scenes, and changed the music on the soundtrack. The character of Rocky loved Bruce Springsteen. His whole room was the Beatles and Bruce Springsteen posters, for God’s sake! They didn’t want to make a deal to use Bruce’s music, so they replaced it with Bob Seger, without my approval. There was a deal to be made, too. Bruce wanted his music to be a part of this film. We had an understanding that if it wasn’t going to be Springsteen, it would be the Beatles! But they made a deal with Seger behind my back. And I like Bob Seger’s music very much, so it had nothing to do with the quality of his work, but it just wasn’t right for the picture. So, I filed a lawsuit which, again, I shouldn’t have done. That was a mess. It hurt the picture and it hurt me. After seeing your original cuts of Mask and Texasville, both of which were tampered with by their studios, it’s amazing how different, and how much better, your cuts are. They’re completely different films than what were released. Yeah, they cut 25 minutes out of Texasville, which was supposed to be a bittersweet picture like Picture Show was. They wound up cutting most of the bitter and keeping in the sweet, which completely threw it off balance. And the thing is, when the schmucks in the executive suite do this to your picture, you as the director are the one who gets blamed, not the studio people who ruined it! I did another film called Illegally Yours (1988), with Rob Lowe, that I had high hopes for, but it was re-cut completely by Dino De Laurentiis. It’s not a good picture, and that’s why. I hope we can do DVDs of the original cuts of Mask and Texasville, which actually was available on Pioneer laserdisc, but is now out of print. We’ll see… (Editor’s note: PB's cut of "Mask" is now available on DVD, as is his black & white cut of "Nickelodeon"). Obviously with 25 minutes added, Texasville is a completely different picture, but it amazed me how different Mask was with just an extra eight minutes and Springsteen on the soundtrack, instead of Seger. Yes, it all counts. It all matters. If you tamper with something like that and remove a part of it, the whole structure comes tumbling down, like a house of cards. The people who run the studios don’t realize this because they’re not filmmakers. But this is nothing new. You can go back to the silent days and filmmakers were treated the same way, like Erich Von Stroheim, whose eight-hour epic masterpiece Greed (1925) was cut down to two hours and twenty minutes by its studio. Think that was a different movie? (laughs) The point is, they know what they’re getting into going into it. To green light a picture that’s built a certain way, and then tear it apart once it’s been completed in that way, does this make sense? You’ve probably had more high highs and low lows than anyone I’ve interviewed in the film business. How do you keep hope alive and keep your chin up during those bad times? I don’t know. (long pause) I don’t know…My mother and father, I suppose, set a fairly good foundation for me, so I haven’t sunk into the earth yet. (laughs) I think they had kind of a sense of art and culture and civilization that they instilled in me that helped give me some strength. Then, of course, there’s my family, and in the case of Dorothy, Dorothy’s family as well. So I was never alone in these things. Some sense of the past, I suppose, also helps. Do you think it’s just a matter of knowing who you are? That doesn’t hurt. A lot of people, especially recently, have experienced tragedy on a huge scale. I think you learn to live with it, as opposed to getting over it. As far as movies are concerned, they pale in comparison to a real life tragedy.  Bogdanovich as Dr. Kupferberg in HBO's "The Sopranos." You’ve been acting a lot again, most notably in Henry Jaglom’s new film Festival in Cannes and in “The Sopranos,” in a recurring role as Dr. Elliott Kupferberg. I love doing that! It’s been a tremendous thing for me to be able to do that, and I’m forever grateful to David Chase for allowing me that opportunity, because a lot of other people would’ve given their eye teeth to be in that show, and he just offered it to me. The other thing I’m very happy about that show is that it’s clarified in a lot of people’s minds that I started out as an actor and have always been aligned to that side of the camera, as opposed to having people think I was a critic. (laughs) What advice would you have for a first-time director? Well, one of the main things is knowing what you want in terms of the scene, so you don’t make your actors do it 17 different ways. At the same time, you want to leave yourself open to the possibility that there might be better ways of doing it. Respect Lady Luck, because she’ll be there sometimes. Also, I would read as much as you can about filmmakers. My book, Who the Devil Made It? was written just for that purpose. I recommend it not because I wrote it, but because it offers a wealth of knowledge from some of the greatest filmmakers of all-time. And that’s where you have to go for knowledge, back to the source.

Bogdanovich as Dr. Kupferberg in HBO's "The Sopranos." You’ve been acting a lot again, most notably in Henry Jaglom’s new film Festival in Cannes and in “The Sopranos,” in a recurring role as Dr. Elliott Kupferberg. I love doing that! It’s been a tremendous thing for me to be able to do that, and I’m forever grateful to David Chase for allowing me that opportunity, because a lot of other people would’ve given their eye teeth to be in that show, and he just offered it to me. The other thing I’m very happy about that show is that it’s clarified in a lot of people’s minds that I started out as an actor and have always been aligned to that side of the camera, as opposed to having people think I was a critic. (laughs) What advice would you have for a first-time director? Well, one of the main things is knowing what you want in terms of the scene, so you don’t make your actors do it 17 different ways. At the same time, you want to leave yourself open to the possibility that there might be better ways of doing it. Respect Lady Luck, because she’ll be there sometimes. Also, I would read as much as you can about filmmakers. My book, Who the Devil Made It? was written just for that purpose. I recommend it not because I wrote it, but because it offers a wealth of knowledge from some of the greatest filmmakers of all-time. And that’s where you have to go for knowledge, back to the source.

0 comments:

Post a Comment