NICOLAS CAGE: BAD TO THE BONE

By

Alex Simon

It’s an inevitable event in every accomplished artist’s life: if you go back on the timeline of their existence and stop in adolescence, almost all of our greatest actors, writers, filmmakers, musicians and painters went through tumultuous, tortured teenage years, often scorned, almost universally ridiculed by their peers and elders alike for the cardinal sin of being “weird.” Most people run from their inner nerd as they grow into adulthood, masking it behind toned muscle, fine clothing and the right haircut, struggling to be that cool guy or gal whom we knew had all the answers and the clearest skin back when such things started to be de rigeur in our lives (and if you live in Southern California, continue to be).

Nicolas Cage is that rare movie star who not only never seemed to care if he was cool, but was one of the few that seemed to run from it, embracing his inner nerd and quirky weirdness wholeheartedly. Yes, he cut quite the impressive figure in the series of box office smash action films he was in: buff bod, cool wardrobe, good with a gun, and almost inevitably got the hot chick in the end, Bond style. However, unlike 007, who is always seen in the final fade out with a dry martini in one hand and a supermodel with a PhD in astrophysics in the other, Nic Cage would turn around wearing horn-rimmed glasses and reading a mint condition issue of Spiderman #2, with a grin that seemed to say “Fuck you Johnny Cool, I’m still a geek!” And herein lies the brilliance of one of our greatest actors.

Cage was born Nicholas Kim Coppola on January 7, 1964 in Long Beach, the youngest of three sons born to August Coppola (who passed from a heart attack in October), a professor of comparative literature, and Joy Vogelsang, a classically trained dancer and choreographer. Born into one of America’s premiere artistic families, Nic’s father is the eldest sibling of filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola and actress Talia Shire. Their father, Carmine Coppola, was an accomplished musician, composer and conductor, and composed much of the music for son Francis’ films, until his death in 1991.

Life was not easy for young Nic, who sought refuge first in his imagination, and then on the stage and in front of the camera. After graduating high school early (he is not a dropout as has been reported in the past), Nic landed his first feature film role (as Nicolas Coppola) in the classic Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) in a part that was mostly left on the cutting room floor. The following year, Nic starred (as the newly-christened Nicolas Cage) in the sleeper hit Valley Girl, which made him one of his generation’s most prolific and acclaimed actors. The momentum hasn’t stopped since, with Nic having starred in over 50 features, producing nine, and directing one (2002’s Sonny). Nic won the 1995 Best Actor Academy Award (as well as a Golden Globe, and the LA and NY Film Critics Award) for his searing performance in Mike Figgis’ Leaving Las Vegas. Nic was nominated in the same category for his brilliant turn as identical twin screenwriters in Adaptation (2003). Whether he’s playing an inbred trailer park denizen who longs to give his wife a child (Raising Arizona, 1987), an Elvis-obsessed hipster on the lam with his true love (Wild at Heart, 1990), or an ambulance driver teetering on the brink of madness (Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead, 1999), Nic Cage is one of the cinema’s great chameleons: although he often changes colors with the diverse parts he plays, his quirky intensity and unpredictability make him completely riveting to watch. Even in some of his lesser films, Cage has never given a lesser performance.

Nicolas Cage gives a no-holds-barred turn in legendary auteur Werner Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, portraying a drug-addicted cop teetering on the brink of insanity, in the post-Katrina Big Easy. A wild, stinging satire rife with Herzog’s trademark haunting, yet beautiful imagery, the First Look Studios release, which co-stars Eva Mendes, Val Kilmer and Alvin "Xzibit" Joiner hits U.S. theaters with a vengeance November 20.

Nic Cage sat down with The Hollywood Interview recently to discuss film, philosophy, and the liberation of embracing your inner nerd. Here’s what transpired:

What was it about Bad Lieutenant which initially attracted you?

Nicolas Cage: I was up for the challenge of it, the risk of it. I’m at a point now where I need to look for work that keeps me interested, keeps me excited about acting. I know Harvey [Keitel], and thought he was excellent in the first Bad Lieutenant, and felt that Abel Ferrara directed a great movie. With Werner and this script, I thought we could take the original Bad Lieutenant and make it a much more abstract film. And New Orleans itself - I have a very close connection with this city. In many ways, I was reborn here; became a philosopher here. It‘s the city that woke me up to the possibility of other ancient energies… and that is both a blessing and a curse. I’ve made four pictures here and this is my fifth. I was afraid to come back and do another movie, but when I’m afraid to do something, I know I have to do it. I have to face the fear, get over it and work through it. These are the main reasons.

Cage and Eva Mendes in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.

Cage and Eva Mendes in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.

You chose the setting for this film. Can you talk about this?

Cage and Eva Mendes in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.

Cage and Eva Mendes in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.You chose the setting for this film. Can you talk about this?

I chose New Orleans for the reasons I previously expressed, and it’s a city like nowhere else in the world. We have a Bad Lieutenant in New York, and because this is a new movie entirely, Bad Lieutenant Port of Call: New Orleans, let’s give it a cultural twist that we haven’t seen before.

What was it like to make a film with Werner Herzog?

What was it like to make a film with Werner Herzog?

Werner had come to me in 1995 to do Cortez, and I had just come off of Leaving Las Vegas. I was being very selective about what I was going to do and not do, and when Cortez came across my desk, I didn’t feel it was wise to play this dictator who was pretty horrific. A lot of actors who play Manson or Hitler, you don’t see them again, and I didn’t want that to happen to me. I was also much younger then. I would have a different way of looking at it now. But to get back to Werner – I grew up watching his movies, and my father and Werner are friends. My father was a huge admirer of Herzog’s work, as are some of my colleagues, and they all recommended that I do it. I really like Nosferatu, Aguirre: Wrath of God and Stroszek. Those are pictures that stand out. I thought it would be good to work with him.

I’m always looking for a new way to express myself. I just did a picture in Bangkok with two Chinese brothers and an all-Thai crew, because I thought they would bring a ‘new me’ out. When you’ve acted for 30 years, you have to find new ways of reinventing yourself, and if you can’t find it on your own, you have to go to strange places and see if they can find it for you. Now, I’m working with a German, a great artist, to see what his sensibilities are. What can he see in me, what can he bring out?

Bad Lieutenant is a self-generated motor. Werner knows this and we’ve worked well together because of this. He lets me do what I need to do, and I let him do what he needs to do. Each of us knows who we are, which always makes it easier.

I’m always looking for a new way to express myself. I just did a picture in Bangkok with two Chinese brothers and an all-Thai crew, because I thought they would bring a ‘new me’ out. When you’ve acted for 30 years, you have to find new ways of reinventing yourself, and if you can’t find it on your own, you have to go to strange places and see if they can find it for you. Now, I’m working with a German, a great artist, to see what his sensibilities are. What can he see in me, what can he bring out?

Bad Lieutenant is a self-generated motor. Werner knows this and we’ve worked well together because of this. He lets me do what I need to do, and I let him do what he needs to do. Each of us knows who we are, which always makes it easier.

Cage confers with director Werner Herzog.

Cage confers with director Werner Herzog.The search for who we are inside is an ongoing quest, isn’t it? It should always keep going, ideally.

Yeah, and it will, until we become…what’s the right way of saying this? Until we’ve overcome it to the point where we can become masters of our own destiny, if such a thing is possible.

We become the directors, not the actors?

(laughs) Yeah, we’re no longer at the mercy of the elements, but more in control of them.

Ever met anybody like that?

No. Have you?

Never. (both laugh) I’ve always wanted to meet The Dhali Lama. I would imagine he’s pretty close to that.

Never. (both laugh) I’ve always wanted to meet The Dhali Lama. I would imagine he’s pretty close to that.

Yeah, that’s what I’ve heard, too. When he walks into a room, you feel a different level of vibration, that he’s that guy we’re talking about.

Cage in Bad Lieutenant.

Cage in Bad Lieutenant.

Your background is the stuff of Hollywood lore now: you’re the offspring of what has become one of the most prolific artistic families in Hollywood history: the Coppolas. Your father August Coppola was a professor of Fine Arts, right?

Cage in Bad Lieutenant.

Cage in Bad Lieutenant. Your background is the stuff of Hollywood lore now: you’re the offspring of what has become one of the most prolific artistic families in Hollywood history: the Coppolas. Your father August Coppola was a professor of Fine Arts, right?

Yeah, comparative literature. He initially taught at Long Beach State and then became Dean of Creative Arts at San Francisco State. Here’s the interesting thing about my father in relation to education: he was pretty frustrated with the educational system, so when I went to him in high school and said ‘Dad, I’m not a good match for this. This isn’t me. I want to go to work. I want to act. High school isn’t working for me.’ He actually said “Go ahead and take the (GED) exam, and get out.” So what one would expect, that he would insist I go to college, wasn’t the case. He encouraged me to follow my dream and go on.

But he was also the son of an artist.

But he was also the son of an artist.

Yeah, so he understood that and related to that. Thank you for pointing that out. It has been somewhat confusing to me over the years why he would say that’s okay. It was somewhat important to him that I pass the equivalency, which I did do. I passed the GED, but I didn’t finish the school year. To set the record straight, I am not a high school dropout, as has been said. I have a diploma. I just wanted to get to work.

Your mother is also an artist, right?

Your mother is also an artist, right?

Yeah, she was a dancer, a modern dance instructor. She studied at UCLA. I was surrounded by that kind of frequency, of artistic energy, that was always around my family. When I’d visit my uncle Francis, it was everywhere. It’s the kind of thing where, it’s madness. There’s a level of it that’s so eccentric and zany, that if you’re not careful, it can catch like wildfire and burn you down. But at the same time, that’s the very stuff that makes people fascinating to watch and charismatic. The trick is, how do you keep a balance with it and not blow yourself out.

Well, the history of art, and particularly cinema, is littered with the corpses of people who were the architects of their own destruction.

Well, the history of art, and particularly cinema, is littered with the corpses of people who were the architects of their own destruction.

In some capacity whether it’s drugs, high speed driving, or just bad behavior, yeah. This is the very thing that I’m thinking about daily, what we’re talking about now, and I’m trying to think how to express it without sounding like I’ve got my head in the clouds. It occurs to me that we’re on this material plane here and we’re born into it, into matter, and so because we’re on this level, it seems like the people who are the most messed up, and have the largest appetites for the material are the ones we find the most charismatic, and the ones we relate to the most and they sort of take the experience of our lives on Earth and tell the stories. So we go to the theater and we see it, and we say “Yeah, I know what that’s like. I’ve been there. I know what it feels like to drink myself into oblivion. I know what it’s like to want to rob a bank,” and so on. But no one wants to go watch a movie about a guy like The Dhalai Lama. Who’s going to want to go watch that for two hours? As beautiful as it is, people seem to be gravitated toward those who are on this plane and who are succumbing to the plane.

It’s called “drama” for a reason. You know the one word definition of drama, don’t you?

No. What?

“Conflict.”

“Conflict.”

Yeah, yeah. It’s something that I’m really contemplating right now. If I became perfect, which I am not (laughs), would anybody want to see my work?

But would you want to be perfect?

But would you want to be perfect?

That depends. It’s almost like if you want to get to another level, assuming there is another level in the afterlife, I’d rather be an eagle than a monkey. But I don’t think anybody wants to watch the eagle. I think they want to watch the monkey.

It’s also comforting, to a certain degree, to watch people who appear to be far more fucked-up than we are, even though that might be the case. Most likely, unconsciously, we’re relating to that pain and that dysfunction far more than we realize. Is that what you’re saying?

It’s also comforting, to a certain degree, to watch people who appear to be far more fucked-up than we are, even though that might be the case. Most likely, unconsciously, we’re relating to that pain and that dysfunction far more than we realize. Is that what you’re saying?

Yeah, yeah, that is what I’m saying. The most charismatic stars and performances: Al Pacino in Scarface (1983), Jack Nicholson in a number of movies, Robert de Niro in Raging Bull (1980), these are people who are really beleaguered with issues, but you can’t take your eyes off of them. I’m not saying the actors themselves are beleaguered, but the characters they play are. If you did become perfect, you would almost have to resacrifice yourself into matter to be able to be someone who would be accessible to people.

You would have to become Keir Dullea 2001: you would just become light spheres.

You would have to become Keir Dullea 2001: you would just become light spheres.

Yeah, exactly! So the artist to me is really the one who, in a sense, is a character who is giving themselves up for the people.

From what I’ve read, you’ve always known that you were an artist, and have marched to the beat of your own drummer from the time you were a small child.

From what I’ve read, you’ve always known that you were an artist, and have marched to the beat of your own drummer from the time you were a small child.

Yeah, that’s right.

Did you know you were an actor at that point, or did you just know you were different?

I knew I was different. I knew in very abstract ways that I wanted to be an actor. I liked what was happening in a box—which was the television set—more than what was happening in my own family living room. I wanted to figure out how to get inside the box. It was mystifying to me, and thought it was amazing that there were people inside this little box. I vowed in my mind that I’d learn how to get inside it.

You were also the victim of bullying growing up because you were perceived as being so different.

You were also the victim of bullying growing up because you were perceived as being so different.

Yeah, those were rough years.

But don’t you also think that when you don’t fit into the norm, it forces you to develop the part of your brain that forces you to create, in order to maintain some kind of stability?

But don’t you also think that when you don’t fit into the norm, it forces you to develop the part of your brain that forces you to create, in order to maintain some kind of stability?

Yeah, it’s a training ground of sorts. Look around, this whole place is a training ground. There’s a million opportunities to not give in, and not have it break your spirit. Instead, you can have it be a stepping stone, depending on how you navigate those waters. Our minds are so sensitive at that age. But I had that moment on the football field where everyone in the school starting backing away, and just slamming me with every other name you could think of, and I didn’t know why it was happening. Although it turned out it was because I was wearing a t-shirt that had The Incredible Hulk on it. (laughs) And that was it, from then on.

You were “it.”

You were “it.”

Yeah, I was “it.” I was the guy with the cooties. But I remember taking a deep breath, and just kind of gliding out of it, and going home and sort of breathing and calming down, and just sort of making a mental note of it, but not letting it become the wildfire that we’re talking about.

Which is what happened at Columbine.

Which is what happened at Columbine.

Yeah, which is what happened at Columbine. You have to have a place which can funnel the negative energy and turn it into a positive. A lot of these kids don’t have that. They have no identity, or that becomes their identity, being an avenging angel, of sorts. If I could have been there, and had been some kind of teacher or something, I would have said ‘What kind of music do you like? Okay, you like goth music. You like it to be really dark and scary. Well, let’s see if we can learn to make it together, to put it all there.’ People get mad at kids when they draw scary pictures, they think it’s the sign of some sort of disturbance. Well, actually it’s art. He or she is taking a scary image, getting it out of their head, putting it onto a piece of paper, and alleviating the pressure. They’re doing something good with it. To take that away, or not facilitate or educate that is why, I think, we have these problems.

Let’s get back to some of your films.

Let’s get back to some of your films.

(laughs) Yeah, okay.

Trailer for Valley Girl.

Trailer for Valley Girl.

The first movie I saw you in was Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982).

I had auditioned for Judge (Reinhold)’s part, and did about ten or twelve auditions for it, and didn’t get it, but got a supporting part as Brad’s Bud #1 or #2, I forget which. A lot of your scenes are on the TV version, that they air on TNT.

Are they really? That’s bizarre. I remember my father driving me to work on that. I was 16. I guess that makes me a child actor, of sorts. It’s been over 25 years now. It’s very interesting growing up publicly. I was there and most of the actors were five or six years older than me, so I was the nerd again. Another mental note was checked off there. (laughs) Like American Graffiti (1973), Fast Times turned out to have this incredible cultural and artistic synchronicity in terms of all the actors who went onto greatness.

Yeah, there was a buzz in the air that there was something excellent being created. It was another difficult time, though. I was Nicolas Coppola, and there was a lot of “Oh, he thinks he can be an actor because he’s Francis Coppola’s nephew.” So again, I had to sort of figure out how to deal with that, and achieve my goals if this is being put on me. Now again, with a very young, very sensitive mind. So it occurred to me that one, I’d have to work twice as hard as the other actors in order to be taken seriously, and two, that I’d have to change my name.  Cage and Deborah Foreman in Valley Girl. So it was between Fast Times and Valley Girl (1983) that Nicolas Cage was born.

Cage and Deborah Foreman in Valley Girl. So it was between Fast Times and Valley Girl (1983) that Nicolas Cage was born.

Cage and Deborah Foreman in Valley Girl. So it was between Fast Times and Valley Girl (1983) that Nicolas Cage was born.

Cage and Deborah Foreman in Valley Girl. So it was between Fast Times and Valley Girl (1983) that Nicolas Cage was born. Right. You got “Cage” from the musician John Cage?

John Cage and also the comic book character Luke Cage. I liked reading comics as boy—I was a nerd—and it was how I learned to read, really. Then I when I went to Horace Mann Elementary School, in music class they talked about John Cage, and I always thought that it was such a cool name. Then I started getting interested in that kind of music, which is what my father listened to. So that was the genesis of the name. After Valley Girl, everything changed for you.

Yeah, that was the first time I felt like I could breathe on a movie. I walked in on that with a new name. Nobody knew who my uncle was. The other actors weren’t teasing me about it, so I suddenly felt like I could really relax and do what I think I can do. All I wanted was to be on the same playing field as everyone else. Not that I have a problem with my name, but don’t have prejudice towards me because of my name. Just put me on the same playing field because I think I can do this, whether you think so or not. So that’s what Valley Girl did for me. You did three movies with your uncle. Since there was a familial bond in place already, did they two of you have a sort of shorthand in terms of how you communicated?

What happened was, Francis saw Valley Girl and got very excited about the possibility of me, and that’s when The Cotton Club (1984) happened, and then Peggy Sue Got Married (1986), and all that stuff occurred. And I liked working with him. I found him to be very open to some far-out ideas. Peggy Sue I didn’t want to do. I actually turned it down originally. He really went through the paces with me on that. TriStar wanted to fire me and he talked them out of it. I was going for something different with that character, and he didn’t know 100% what he was getting into when he cast me. I told him I didn’t quite know why he wanted to make the movie, and he said “Well, it’s like Our Town.” So I kept turning him down, and finally I gave in on the condition that I could go pretty far out with the character. During rehearsal, I came up with this idea to into Pokey from the Gumby show, and create this cartoon character. Those were some very tense days on the set. Every day I was going to be fired. Kathleen (Turner) was not happy with the performance. She thought she was going to get the boy from Birdy (1984) and instead she got Jerry Lewis on acid! (laughs)  Cage in Francis Coppola's Peggy Sue Got Married. But that interpretation was so appropriate, because that guy, in every high school in America, is a cartoon!

Cage in Francis Coppola's Peggy Sue Got Married. But that interpretation was so appropriate, because that guy, in every high school in America, is a cartoon!

Cage in Francis Coppola's Peggy Sue Got Married. But that interpretation was so appropriate, because that guy, in every high school in America, is a cartoon!

Cage in Francis Coppola's Peggy Sue Got Married. But that interpretation was so appropriate, because that guy, in every high school in America, is a cartoon! Exactly! Not only that, but the dreamscape that we were playing in was very exciting to me. So I thought since this is about the visions a woman has when she’s fainted, maybe I could make Charlie a little more abstract. Every time that movie’s brought up today, it’s your performance that people talk about.

That’s what’s so ironic because at the time, it was really lambasted critically. “The wart on an otherwise beautiful movie,” is what one critic said, I think.

Cage and Laura Dern in David Lynch's Wild at Heart. Wild at Heart (1990) is one of those movies that keeps getting better every time I see it. Although I have to admit when I first saw it, I hated it.

Cage and Laura Dern in David Lynch's Wild at Heart. Wild at Heart (1990) is one of those movies that keeps getting better every time I see it. Although I have to admit when I first saw it, I hated it. You know what’s interesting about what you’re saying now, is I’ve notice this happen with all kinds of art forms. Apparently 2001 got slammed when it came out. Rock Hudson walked out of the theater. The very things that really kind of rub us the wrong way at first, become the things we connect with so deeply later. That’s why I think I get as happy with the bad reviews as I do with the good ones. I don’t want to make people too comfortable right off the bat. If I can really do my job well and get to the truth of something, inevitably that might be a little bit painful. (laughs) And that’s why I try to be careful with the movies I choose. I don’t want to have one identity. I want to keep looking for different points of expression. Anytime you elicit a strong emotional response from someone, you know you’re doing your job.

You know you’re doing something right, absolutely. Owen Glieberman from Entertainment Weekly gave Lord of War a D-, which is basically failing the movie. So I thought ‘Okay, I know it’s not a D-, otherwise we wouldn’t have David Denby from Newsweek saying it’s one of the most enjoyable movies of the year.' He’s a very important critic. So to me, those are very interesting polarities and it says I know I’ve gotten you, Owen. I know I’ve affected you in a way that you’re going to think about this down the road. So it’s actually a good review, if you think about it that way. I actually told them to put (Glieberman’s grade of D-) on the poster, but Lions Gate wouldn’t do it. (laughs)

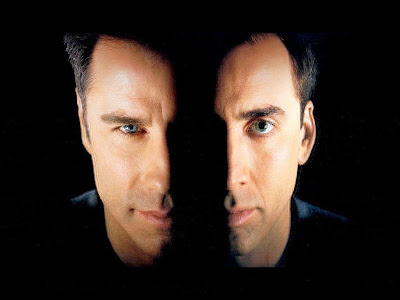

Cage in his Oscar-winning turn in Leaving Las Vegas, with Elizabeth Shue. Tell us about the experience of making Leaving Las Vegas (1995) and working with Mike Figgis. It was just a great time, all the way around. I had a great connection with Mike and Elisabeth Shue. Mike is music. He’s free form and rhythm and melody and it comes out in his direction. He’s even got music on the set that he was composing. So we had a connection and I hope to work with him again some day. We did the film very quickly, in about four weeks and it just was painless, I don’t know why. It just seemed like everything was linking up. It was channeled with the real guy, John O’Brien, almost. (Editor’s note: John O’Brien, who wrote the novel on which the film was based, committed suicide shortly before principal photography started) I felt like I was making moves that I later on found out he had made, like the way he’d light his matches. The car he drove, Mike wanted him to drive an old Jaguar and I said ‘No, he should drive a BMW, like every other agent in town.’ And he had a BMW, and I didn’t know that. His parents came to the set and would comment on how much I reminded them of their son. I don’t want to get too spooky about it, but it was a very special time. We were in John’s mind somehow. John Woo is one of my favorite directors, and I’m a big fan of Face/Off (1995).Tell us about that. Face/Off for me is a personal milestone because I felt like I was able to realize some of my independent filmmaking dreams in a major studio film. I was taking a lot of the laboratory of Vampire’s Kiss (1989) and points of expression that I was working on with films like Nosferatu (1922) or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919): early German expressionistic film acting, and with Face/Off, I got do it in a huge genre picture. John had shown me his film Bullet in the Head (1990) and I knew when I saw that where he would let me go. I knew his barometer and that I could put it up against a wall of expressionistic acting, as opposed to naturalistic acting. I’d not done that to that level before in a big studio movie, so it was a real personal best for me. I got to get way outside the box.

Cage in his Oscar-winning turn in Leaving Las Vegas, with Elizabeth Shue. Tell us about the experience of making Leaving Las Vegas (1995) and working with Mike Figgis. It was just a great time, all the way around. I had a great connection with Mike and Elisabeth Shue. Mike is music. He’s free form and rhythm and melody and it comes out in his direction. He’s even got music on the set that he was composing. So we had a connection and I hope to work with him again some day. We did the film very quickly, in about four weeks and it just was painless, I don’t know why. It just seemed like everything was linking up. It was channeled with the real guy, John O’Brien, almost. (Editor’s note: John O’Brien, who wrote the novel on which the film was based, committed suicide shortly before principal photography started) I felt like I was making moves that I later on found out he had made, like the way he’d light his matches. The car he drove, Mike wanted him to drive an old Jaguar and I said ‘No, he should drive a BMW, like every other agent in town.’ And he had a BMW, and I didn’t know that. His parents came to the set and would comment on how much I reminded them of their son. I don’t want to get too spooky about it, but it was a very special time. We were in John’s mind somehow. John Woo is one of my favorite directors, and I’m a big fan of Face/Off (1995).Tell us about that. Face/Off for me is a personal milestone because I felt like I was able to realize some of my independent filmmaking dreams in a major studio film. I was taking a lot of the laboratory of Vampire’s Kiss (1989) and points of expression that I was working on with films like Nosferatu (1922) or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919): early German expressionistic film acting, and with Face/Off, I got do it in a huge genre picture. John had shown me his film Bullet in the Head (1990) and I knew when I saw that where he would let me go. I knew his barometer and that I could put it up against a wall of expressionistic acting, as opposed to naturalistic acting. I’d not done that to that level before in a big studio movie, so it was a real personal best for me. I got to get way outside the box.  Cage and John Travolta in a publicity still from John Woo's Face/Off. I forgot that you executive produced Shadow of the Vampire (2000), which was a fictional re-telling of the production of Nosferatu. F.W. Murnau, who directed the latter film, is one of my heroes. Yeah, he was amazing. Sunrise (1927) is one of the greatest films ever made. Nosferatu actually changed my life when I saw it as a kid. It’s one of the movies that made me fall in love with movies and scared me to the depths of my soul. It’s kismet that we’re talking because that’s exactly the same experience I had. My father used to bring the movies home from Cal State and he’d project them for us, and there I was, looking at this terrifying imagery. It was so uncomfortable and really made me miserable but again, like we talked about, I began to fall in love with it. Murnau shot it like a documentary, which is what made it so interesting. Wasn’t it one of the first films to go on location? I think it might have been, yeah. What we did in Shadow of the Vampire was pretty thought-out and accurate in terms of the actual events, except of course that (actor) Max Schreck wasn’t really a vampire! (laughs) All actors by some definition are vampires, I suppose. I have a theory that all great actors and filmmakers have one overlooked masterpiece, and I think 8mm (1999) is yours. I think it’s such a brave, audacious, deeply disturbing movie. Thank you. I’m sure Joel (Schumacher) will be happy to hear that. In a lot of ways that movie is kind of a milestone for me, because it’s my first foray into horror. To me, it’s a horror film, and I hadn’t really done that before. It does have weight in my library, but it was, as you said, overlooked and wasn’t something people could respond to at the time because it was so dark and disturbing. It’s not how people want to spend eight bucks to get their minds off their problems. (laughs)

Cage and John Travolta in a publicity still from John Woo's Face/Off. I forgot that you executive produced Shadow of the Vampire (2000), which was a fictional re-telling of the production of Nosferatu. F.W. Murnau, who directed the latter film, is one of my heroes. Yeah, he was amazing. Sunrise (1927) is one of the greatest films ever made. Nosferatu actually changed my life when I saw it as a kid. It’s one of the movies that made me fall in love with movies and scared me to the depths of my soul. It’s kismet that we’re talking because that’s exactly the same experience I had. My father used to bring the movies home from Cal State and he’d project them for us, and there I was, looking at this terrifying imagery. It was so uncomfortable and really made me miserable but again, like we talked about, I began to fall in love with it. Murnau shot it like a documentary, which is what made it so interesting. Wasn’t it one of the first films to go on location? I think it might have been, yeah. What we did in Shadow of the Vampire was pretty thought-out and accurate in terms of the actual events, except of course that (actor) Max Schreck wasn’t really a vampire! (laughs) All actors by some definition are vampires, I suppose. I have a theory that all great actors and filmmakers have one overlooked masterpiece, and I think 8mm (1999) is yours. I think it’s such a brave, audacious, deeply disturbing movie. Thank you. I’m sure Joel (Schumacher) will be happy to hear that. In a lot of ways that movie is kind of a milestone for me, because it’s my first foray into horror. To me, it’s a horror film, and I hadn’t really done that before. It does have weight in my library, but it was, as you said, overlooked and wasn’t something people could respond to at the time because it was so dark and disturbing. It’s not how people want to spend eight bucks to get their minds off their problems. (laughs)  Cage in Joel Schumacher's 8mm. If it had been made in 1971, it would have been a hit.

Cage in Joel Schumacher's 8mm. If it had been made in 1971, it would have been a hit. But you see, those are my favorite movies, from the 70s. I’m still kind of living that fantasy, trying to do it in 2005. But that was the time, and those were the movies that propelled me into wanting to go for this. The 50s and 70s movies for me are the ones that got me on the track of wanting to be an actor. I was watching Klute the other day, which was made in 1971. A movie from 1985 is more dated now than that film is.

Yeah, right. I believe that. If you look at A Clockwork Orange (1971), it’s like virtual reality now. Even if you take a single frame of that film, the amount of time Kubrick must have put into lighting that, it just pops! The shot of the droogies as they’re walking out of the milk bar, it’s lit in a way that’s nearly digitally perfect, and he did it in ’71. It’s fascinating. Tell us what directing was like, with Sonny (2002). That was a great experience, too. It was a real highlight for me. I was surrounded by some of my favorite actors. I’ve never seen James Franco hit a false note. He’s a great actor, and he’s just fantastic in the movie. It’s a great kitchen sink drama. Did you study the films of Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson before you did it? No, I didn’t. It just kind of came out of me, the way I sort of felt it. I didn’t want to take too much away from the actors. I wanted the film to look beautiful, but I really just wanted to focus on performance, and I got that. I was very happy with the results.

0 comments:

Post a Comment