CLIVE OWEN GETS BACK

By

Alex Simon

Clive Owen is one of those actors that keep surprising you. Just when you think the audience, and the Hollywood establishment, has pegged him as an action hero, a leading man, or a romantic comedy pin-up, Owen pulls an about-face and does something unexpected.

It all started October 3, 1964 in Coventry, England. Owen’s father, a country music singer, abandoned the family when he was just three. His mother later remarried, with Clive and his four brothers raised by his mother and stepfather, who worked for British Rail. Owen has characterized those early years as "rough." A self-described “solidly working class” kid, Owen was bitten by the acting bug at age 13 and followed his dream to The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art several years later. Initially cutting his teeth on high-profile British television programs such as “Chancer” and “Sharman,” as well as art house features Close My Eyes (1991), Century (1993) and Bent (1997), Owen hit paydirt with the title role in Mike Hodges’ thriller Croupierin 1998, playing an aspiring writer whose night job as a croupier in a London casino begins to slowly corrupt his existence.

Owen became an international sensation seemingly overnight, with rumors circulating that he would be the next James Bond as soon as then-007 Pierce Brosnan’s contract was up. The rumor mill never grew hotter than when Owen starred in BMW’s now-classic series of The Hire shorts as “The Driver,” each helmed by legendary action directors such as John Frankenheimer and Tony Scott. Although he (supposedly) was never offered the role of the martini-drinking superspy, Owen managed to dazzle audiences and critics alike in such prestige titles as Robert Altman’s Gosford Park (2001), The Bourne Identity (2002),Mike Hodges' I'll Sleep When I'm Dead (2004) King Arthur (2004) playing the eponymous role, Mike Nichols’ Closer (2004), reprising his part from the original London stage production, Frank Miller’s Sin City (2005), Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006), and Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men (2006). In the last year, Owen has headlined Tom Tykwer’s The International, and Tony Gilroy’s Duplicity.

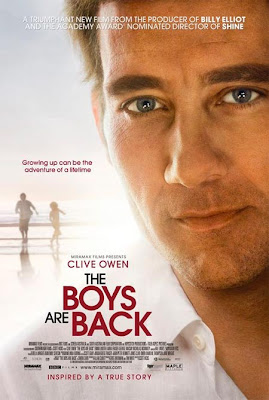

The Boys Are Back, based on Simon Carr’s memoir, marks another change of pace for Clive Owen, playing British journalist Joe Warr, a fiercely driven sports writer who now lives Down Under (Australia, for those not in the know), and finds his life turned upside down upon the sudden death of his wife, leaving Joe to care for their young son (newcomer Nicholas McAnulty). To complicate matters, Joe’s estranged teenage son from his first marriage (George MacKay) arrives from the UK to comfort his bereaved father. Director Scott Hicks avoids the sentimental pitfalls that could have put this fine drama in movie-of-the-week territory, and delivers a quiet, powerful human drama that is also full of honest humor and terrific performances. The Miramax release opens in U.S. theaters September 25.

We sat down with Clive Owen during his recent stopover in Los Angeles to discuss his latest offering, as well as films and plays past. Here’s what followed:

This is a different kind of role for you. What drew you to the project initially?

Clive Owen: The same thing every time: it was a really good script, and Scott Hicks, those were the two things. I was very affected by the script the first time I read it. It was very beautifully-written, very honest exploration of parenting from a guy’s perspective, which was very full, very emotional. I thought Scott was the perfect guy to direct it because he’s got sensitivity, and an intelligence and a delicacy about him. This is a very intimate film, and it demanded that, since two of the three main characters were children, so it demanded that. You need someone with patience and understanding, and that’s why I wanted to do it.

L to R: George MacKay, Clive Owen and Nicholas McAnulty in The Boys Are Back.

L to R: George MacKay, Clive Owen and Nicholas McAnulty in The Boys Are Back.Since you were dealing with interacting with children, one very young one in particular, how important was it for you to develop that bond with them on-set prior to filming?

It’s everything. In our first conversation, me and Scott, we said the key to the film falls into finding the right boy to play the youngest son, and the audience believing the bond, and believing the relationship between our two characters. So I made sure I got to the set very early and spent time with (Nicholas) very early. I took him to safari parks and fun fairs and away from his parents, away from the film crew. So whatever happens during the film, because much of the film is quite tough between the two of us, he trusted me. He’d always come back to the place of “I’m okay with Clive,” even if we’d just done a scene that was a little unusual or emotional. It was important that he felt safe with me, and I had to put that time in.

Nicholas McAnulty and Clive Owen horse around on the set in Adelaide, Australia.

Nicholas McAnulty and Clive Owen horse around on the set in Adelaide, Australia.Was there any resistance from Nicholas in the beginning to forge that bond, or did he leap into it?

No, he leapt into it. He’s a very intelligent, open kid. For sure it was important that I did it. There was no way I could have just gone in cold without meeting the kids beforehand and shot the movie. It always takes time with kids, to establish that trust factor. Once we started making the film, he’s so bright and there were never any problems.

I really liked the relationship between your character and your elder son. That’s something that hasn’t been dealt with in a lot of feature films: the issue of abandonment when one parent starts a new family.

(George MacKay) is a fine actor. He’s a seriously fine actor, and I was really impressed with him. There’s no accident with what he’s doing. George is just skilled beyond his years. He’s a very full actor, even when he’s not speaking, there’s always a lot going on. Him coming into the film at that point, I just felt when I saw what he was doing, that he would be very moving without him even doing much physically. I knew the audience would find him moving. They’d just feel the history, and what he felt he’d missed, and so I just think he was a great find for the film. I was hugely impressed with him.

Nicholas McAnulty, Clive Owen and Emma Booth in The Boys Are Back.

Nicholas McAnulty, Clive Owen and Emma Booth in The Boys Are Back.There are a lot of very emotional scenes in this film, but it never crossed the line into melodrama. How do you find that place as an actor, yet keep it real enough that you don’t cross over that line?

Well, it helped that I found the idea so upsetting myself. The idea of explaining to my little boy that his mother might not be around much longer, I find that very upsetting and tragic as an idea. I’ve got two girls, so the idea of that conversation is just haunting to me. So that’s the gist of it really: I relate to it. When it comes to actually doing the work, it’s about concentration and putting yourself in the place of your character, but ultimately, it’s because I understand and relate to the emotions that are there on the page and in the scenes.

Owen in Mike Hodges' Croupier, the film that made him a star.

Owen in Mike Hodges' Croupier, the film that made him a star.You mentioned that working with Scott was one of the things that attracted you to the film. Looking over your filmography, you’ve been very careful in choosing some great directors, none more so than Mike Hodges, an unheralded great director who should have a citation from God for Get Carter alone, who gave you your first big break, and with whom you’ve now worked twice.

Yeah, his little film Croupier was the film that changed everything for me, and is one of the best writer/directors out there. It’s crazy that he’s not more famous, because he’s so original and skilled, but he’s also fiercely independent and does things his own way, which is what gives his work the power that it has. Mike’s a friend, he always will be, and I’ll always remember that he was the one who gave me that first opportunity which changed my career.

You worked with two other legendary directors who are sadly no longer with us: John Frankenheimer and Robert Altman.

Oh yeah, I got on fantastically with both of them. Frankenheimer was such a great character and such an amazing director. We had a long conversation shortly before he passed away about working together again, we got on so well. Altman was undoubtedly one of the greatest directors there’s ever been: his knowledge of film, his ability to put dozens of storylines into a single film and make it look so easy, he was so deceptive. He was quite brilliant in terms of the way he made his films. Many directors struggle with having four people in the room in terms of trying to cover it. Bob could put twenty people with twenty different storylines in a room and make it look like the easiest thing. His was an extraordinary talent.

Owen as The Driver in John Frankenheimer's The Hire: Ambush. I’ve heard people liken him to an orchestra conductor. Yes, that’s exactly it. Some of those big scenes, it was like he was putting music together, the way he’d thread things in and make it richer and richer, and more and more layered. He was a great man.

Owen in Robert Altman's Gosford Park. What’s Scott’s approach like in terms of his relationship with his cast? Well, his prescience with young Nicholas was the key, really, because everything was structured around that. He made the crew very much on their toes, like we could change direction at any point today because Nicholas is tired today, and just because it’s very tiring for everyone on a movie set, even more so for a child: the kind of tension, the kind of demands being made on him every day. So we kept very loose, not only in terms of capturing magic, if Nicholas did something suddenly that was really real and alive, we’d try to shoot it. There are a number of moments in the film that were just sort of captured, where Nicholas did something unexpected, or he wasn’t quite aware we were filming, and that demands a real sort of lightness of touch and a huge patience and real understanding on the part of a director. So Scott’s terribly intelligent, terribly sensitive, and I really loved the way he put the whole thing together.

Owen in Robert Altman's Gosford Park. What’s Scott’s approach like in terms of his relationship with his cast? Well, his prescience with young Nicholas was the key, really, because everything was structured around that. He made the crew very much on their toes, like we could change direction at any point today because Nicholas is tired today, and just because it’s very tiring for everyone on a movie set, even more so for a child: the kind of tension, the kind of demands being made on him every day. So we kept very loose, not only in terms of capturing magic, if Nicholas did something suddenly that was really real and alive, we’d try to shoot it. There are a number of moments in the film that were just sort of captured, where Nicholas did something unexpected, or he wasn’t quite aware we were filming, and that demands a real sort of lightness of touch and a huge patience and real understanding on the part of a director. So Scott’s terribly intelligent, terribly sensitive, and I really loved the way he put the whole thing together.  L to R: director Scott Hicks, Clive Owen, and Nicholas McAnulty. You mentioned that you have two girls and this film is from a very male perspective, about a man with two boys. How would the dynamic have been different with two daughters? I think the energy levels are very different. I find that with children the same age as mine who are boys, the energy levels are much higher. Girls are more reserved, generally. I don’t think it would have been quite as volatile, really, with two girls. Girls are calmer. It’s a very interesting question, because I think it would be much easier raising two girls on your own, simply because girls tend to be ahead in their maturity stage in terms of the way they deal with things. How tough is it to find a good script? Hard. (laughs) Very hard. And the only way to find a good one is to read a lot. Every now and again you get to say ‘Here’s a great one.’ Considering how many films are made and how many scripts are written, it’s really rare to come up with a great script, so you really notice it when one crosses your path. You read a lot and suddenly you’re like ‘Oh my God!’ when you find something of real quality. Is that the key to career longevity: choosing quality over quantity? After Croupier there was an attempt to turn you into a kind of “suave action hero,” but you resisted being typecast, and are now known for turning down a lot of big projects in favor of those that resonate with you more personally. I don’t really have a plan in that way, and honestly if you look at the last few years I’ve done, that shape is completely unplanned. There’s no rhyme or reason to it. It’s instinct. It’s something I want to explore. And I’m not going to do something because it’s the “right” kind of thing to do, or I should be doing “that” kind of film. I’m wide-open. I’ll do any kind of film if I think I’ve got something to offer in it, and it resonates, and I believe in it and I think it’s worthwhile doing. Then the career just is what it is. There was no plan there. That’s just the way it’s gone. Parenting is a huge part of my life. I’ve got two girls. Outside the movies, that’s what I do. I bring my girls up, and hang with my girls, and here was a chance to explore that idea fully, which I’ve never gotten a chance to do before. So that’s why I wanted to do it.

L to R: director Scott Hicks, Clive Owen, and Nicholas McAnulty. You mentioned that you have two girls and this film is from a very male perspective, about a man with two boys. How would the dynamic have been different with two daughters? I think the energy levels are very different. I find that with children the same age as mine who are boys, the energy levels are much higher. Girls are more reserved, generally. I don’t think it would have been quite as volatile, really, with two girls. Girls are calmer. It’s a very interesting question, because I think it would be much easier raising two girls on your own, simply because girls tend to be ahead in their maturity stage in terms of the way they deal with things. How tough is it to find a good script? Hard. (laughs) Very hard. And the only way to find a good one is to read a lot. Every now and again you get to say ‘Here’s a great one.’ Considering how many films are made and how many scripts are written, it’s really rare to come up with a great script, so you really notice it when one crosses your path. You read a lot and suddenly you’re like ‘Oh my God!’ when you find something of real quality. Is that the key to career longevity: choosing quality over quantity? After Croupier there was an attempt to turn you into a kind of “suave action hero,” but you resisted being typecast, and are now known for turning down a lot of big projects in favor of those that resonate with you more personally. I don’t really have a plan in that way, and honestly if you look at the last few years I’ve done, that shape is completely unplanned. There’s no rhyme or reason to it. It’s instinct. It’s something I want to explore. And I’m not going to do something because it’s the “right” kind of thing to do, or I should be doing “that” kind of film. I’m wide-open. I’ll do any kind of film if I think I’ve got something to offer in it, and it resonates, and I believe in it and I think it’s worthwhile doing. Then the career just is what it is. There was no plan there. That’s just the way it’s gone. Parenting is a huge part of my life. I’ve got two girls. Outside the movies, that’s what I do. I bring my girls up, and hang with my girls, and here was a chance to explore that idea fully, which I’ve never gotten a chance to do before. So that’s why I wanted to do it.  Owen in Sin City. Did you meet (author) Simon Carr prior to playing the film version of him? I waited till near the end. I really responded to the script and to the memoir, but I didn’t want to see him, or have any kind of physical impression: the way he looked, the way he spoke, the way he carried himself. I needed to be free to interpret it, and I had my own instincts about the part. I got enough from the memoir, which was full of his personality, but I thought it was best to freely interpret rather than get influenced by him. Were you one of those kids that always wanted to be an actor? Yeah, always. I played the Artful Dodger in a school production of “Oliver!” when I was 13, and from then on, that’s what I wanted to do. And I was lucky that there was a youth theater in my home town that I was able to join, and I did a whole host of plays there. You grew up outside of London, right? Yeah. In the suburbs. What did your parents do? My stepfather worked for British Rail and my mother was a housewife. We were solidly working class. Was it tough to be a working class kid to aspire to be an actor? Very. Being where I was from, it just wasn’t something that most people aspired to, so the only option I really had was to get into some sort of accredited drama school. There was no way, given where I came from, that I was going to walk into a life of theater and the movies. The plug-in was that I was hugely fortunate when I applied for The Royal Academy (of Dramatic Art) in London, and managed to get a place. What was the experience of RADA like? Amazing. Suddenly I’m thrown in with people like me, who had the same passion and every day was exploring and discovering new things about what I loved doing. The last year, you do seven plays, seven productions and seven different parts. You’re working with the top-end teachers in that world. And there’s a security there. Once you leave, then you have to get cast in something. You knew you were going to get cast in something when you were there. (laughs) It was a great time. There’s something about doing theater and doing a lot of different parts that really does give an actor a unique sort of grounding. This could have very easily have moved into movie-of-the-week territory, both behind and in front of the camera. Can you talk a bit more about how you all worked to keep it honest and on the other side of the melodramatic line? It was something I was very passionate about from the beginning, which was to avoid the sentimentality. I was really interested in the story’s tougher elements, when things weren’t going well, like when the little boy has his tantrum, and how to deal with that. That was real. It was something we can all relate to as parents, because we’ve all dealt with it. We’re not bad parents because of it. It’s just what happens. There was something very human and understandable about this to me. As you say, there are endless versions of “Mummy’s about to die,” and we weep, and we hug… Cue the violins… Yes exactly, cue the violins. It’s not like that. Parenting is much more volatile. It’s up, down and around. So I wanted to do that in a sort of fearless way, because I knew people would relate to it.

Owen in Sin City. Did you meet (author) Simon Carr prior to playing the film version of him? I waited till near the end. I really responded to the script and to the memoir, but I didn’t want to see him, or have any kind of physical impression: the way he looked, the way he spoke, the way he carried himself. I needed to be free to interpret it, and I had my own instincts about the part. I got enough from the memoir, which was full of his personality, but I thought it was best to freely interpret rather than get influenced by him. Were you one of those kids that always wanted to be an actor? Yeah, always. I played the Artful Dodger in a school production of “Oliver!” when I was 13, and from then on, that’s what I wanted to do. And I was lucky that there was a youth theater in my home town that I was able to join, and I did a whole host of plays there. You grew up outside of London, right? Yeah. In the suburbs. What did your parents do? My stepfather worked for British Rail and my mother was a housewife. We were solidly working class. Was it tough to be a working class kid to aspire to be an actor? Very. Being where I was from, it just wasn’t something that most people aspired to, so the only option I really had was to get into some sort of accredited drama school. There was no way, given where I came from, that I was going to walk into a life of theater and the movies. The plug-in was that I was hugely fortunate when I applied for The Royal Academy (of Dramatic Art) in London, and managed to get a place. What was the experience of RADA like? Amazing. Suddenly I’m thrown in with people like me, who had the same passion and every day was exploring and discovering new things about what I loved doing. The last year, you do seven plays, seven productions and seven different parts. You’re working with the top-end teachers in that world. And there’s a security there. Once you leave, then you have to get cast in something. You knew you were going to get cast in something when you were there. (laughs) It was a great time. There’s something about doing theater and doing a lot of different parts that really does give an actor a unique sort of grounding. This could have very easily have moved into movie-of-the-week territory, both behind and in front of the camera. Can you talk a bit more about how you all worked to keep it honest and on the other side of the melodramatic line? It was something I was very passionate about from the beginning, which was to avoid the sentimentality. I was really interested in the story’s tougher elements, when things weren’t going well, like when the little boy has his tantrum, and how to deal with that. That was real. It was something we can all relate to as parents, because we’ve all dealt with it. We’re not bad parents because of it. It’s just what happens. There was something very human and understandable about this to me. As you say, there are endless versions of “Mummy’s about to die,” and we weep, and we hug… Cue the violins… Yes exactly, cue the violins. It’s not like that. Parenting is much more volatile. It’s up, down and around. So I wanted to do that in a sort of fearless way, because I knew people would relate to it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment