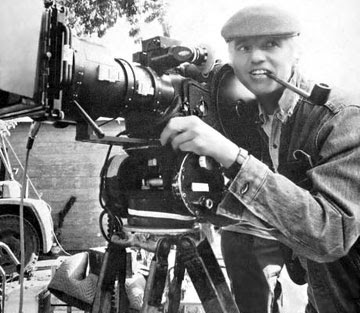

Filmmaker and cinematographer Haskell Wexler.

Filmmaker and cinematographer Haskell Wexler.HASKELL WEXLER SHOOTS FROM THE HIP

By

Alex Simon

Two-time Academy Award-winning cinematographer Haskell Wexler was adjudged one of the ten most influential cinematographers in movie history, according to an International Cinematographers Guild survey of its membership. He won his Oscars in both black & white and color, for Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and Bound for Glory (1976). He also shot much of Days of Heaven (1978), for which credited director of photography Nestor Almendros -- who was losing his eye-sight, won a Best Cinematography Oscar. In 1993, Wexler was awarded a Lifetime Achievement award by the cinematographer's guild, the American Society of Cinematographers. He has received five Oscar nominations for his cinematography, in total, plus one Emmy Award in a career that has spanned six decades.

Born in Chicago to a wealthy family on February 6, 1922, Wexler cut his teeth shooting industrial films, TV commercials and documentaries. He later graduated to shooting television shows, including “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.” Wexler’s big break came in 1962, when Elia Kazan hired him to shoot America, America, after which he became one of Hollywood’s most in-demand cameramen, and literally has not stopped working since. In addition to his masterful cinematography, Wexler directed the seminal late sixties film Medium Cool (1969), which was shot in and around the riots of the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and has directed and/or shot many documentaries that display his progressive political views, including Who Needs Sleep? (2002), a look at the deplorable conditions that many Hollywood crew members are forced to work under, and the start of the “12 On/12 Off” movement, spearheaded by Wexler and the late Conrad Hall. Wexler was the subject of a warts-and-all 2004 documentary shot by his son Mark, Tell Them Who You Are, which detailed not only his father’s remarkable career, but their complicated, and often combative relationship. Wexler’s latest film as cinematographer is Daniel Raim’s documentary Something’s Gonna Live.

Ten years in the making, Something’s Gonna Live is an intimate portrait of life, death, friendship and the movies, as recalled by some of Hollywood’s greatest cinema artists, capturing the late life coming together of renowned art directors (and pals) Robert “Bob” Boyle (North by Northwest, The Birds), Henry “Bummy” Bumstead (The Sting, most of Clint Eastwood’s films as a director) and Albert Nozaki (The War of the Worlds, The Ten Commandments), storyboard artist Harold Michelson (The Graduate, Star Trek: The Motion Picture), as well as master cinematographer Conrad Hall (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, American Beauty), and Haskell Wexler himself. As the film's slogan goes: "6 Men. 25 Oscar nominations. 400 films. 300 years in movies." That says it all.

Now 88 years-old, Wexler is the last surviving member of the film’s cast, and shows no signs of slowing down, promising “I’m as ornery as ever.” Haskell Wexler sat down with The Interview recently in his beachfront apartment to discuss projects past and present, as well as give us a piece of his very active mind regarding the state of our world. Here’s what transpired.

Okay, so why don't we begin talking about the new film, Something's Gonna Live? Tell me how it came about for you. Did the director approach you initially, to shoot the picture?

Daniel knew I was friends with Bob Boyle, and, yeah, he asked me if I could help him on it.

And it was, what, ten years in the making?

Yeah.

Were you friends with all the people? I know obviously you and Conrad Hall were close, and you and Bob Boyle were close. Were you close with Henry Bumstead, and the others?

No, I just knew them by reputation. And I really, the first time I ever talked with them is what you see in the film, when they came out and got together, and their tour of Paramount, and talks in the car.

Right. I was lucky enough to know Bob Boyle when I went to AFI, and thought he was a remarkable guy, just a real craftsman.

Yes, and what they added to it in the film, or what you could see in the film -- which was my praise to the film -- is Bob’s remarkable craftsman view of the world, and tried to approach his work with the same way as he looked at the world and his family. Our kids went to the same school, I drove his kid in the carpool and we switched off.

L to R: Haskell Wexler, Robert Boyle, Daniel Raim.

L to R: Haskell Wexler, Robert Boyle, Daniel Raim.Well, it was obvious that the two of you are very comfortable around each other, because you got some really terrific intimate shots of him just sitting at home, which I thought revealed a lot, without him actually saying anything.

One of the points that's in the film, and that I like about it, is that so much of filmmaking is the different departments: This is this, this is this, this is that. I worked with Bob Boyle I think on three films, and, as a director of photography, I know that what's in front of the camera is eighty percent of what is -- that means, not just the actors, it's everything that you see, so what's on the screen is the result of a lot of people's work. Even beyond the art director to the prop department, the grips, everybody has a part of that creative image, and everything in our system can't just say who did what, how -- but certainly the relationship between how things look and the art directors, we used to call 'em, and the camera, [it's] very, very intimate.

When you look at the stuff he did for Hitchcock, I mean, he was, next to Mr. Hitchcock, the primary factor in what made those films so special.

Yeah. I was sort of surprised that they used the scene from Thomas Crown Affair, the sail-plane. I think Daniel Raim took that because I was giving him an example of the cooperation of the different departments in the filmmaking, and when we saw the dailies of the sail-plane scene in Thomas Crown Affair, I thought it was really boring. And then when they used the Michelle Legrand's "Windmills of My Mind" music, and the Bergman's words to those shots, the photography became great. (laughs) So I was hoping he would use that in the film to demonstrate that, because, to demonstrate, but, to you (use) as Bob Boyle' work, is not as good as, say, the room where they play chess, which was an incredibly art-directed room, and many of his interiors were superb.

Well, that's the scene that I remember most, is the chess game. That's the one that everybody remembers.

Well, you know, it said on the script, it said, 'They play chess with sex,' or some euphemism statement, and so Norman said to me, 'Well, do something,' so they left me pretty much alone with Faye and Steve, and there are a lot of really dirty stuff in there (laughs). I think they left in where she massages one of the chess men in a masturbatory fashion. (laughs)

The "chess" scene in The Thomas Crown Affair, shot by Wexler. She fellates the knight. I mean, she full-on fellates it, and in 1968, that must have been unprecedented. I had no idea that it would even be in the film. And, of course, Faye had to play everything straight, and so did Steve, which they did. Well, that scene, the lighting was just so amazing in that scene. Do you remember how long it took you to light that? No, it was real simple. I mean, I think we just, I think I had the Chinese lantern, and the whole thing was to give the lighting of people this top, soft light that was low enough to get into their eyes. And then of course a lot of the inserts, the close stuff, were shot separately. Sure. And, but then also the sense of the room behind them, you wanted it dark but you have to pick up certain parts of it (something frame) so you have a sense of place, and still keep it very subdued. Right. Actually, do you spend a lot of time lighting, or do you just know what you want and you work pretty quickly generally? No. I mean, every producer I've ever worked for thinks that you spend too much time lighting because they think of lighting as illumination. At least in those days, if you have enough light to shoot the picture, what are you fucking around for? And...that's a good question. (laughs) So what's your answer to it? My (question is) what are we fucking around for? Because we want to make it look more interesting, look like it should look for the mood of the scene, and I'm sure that individually the producers know that and think that, but when the dollar sign and the shooting schedule infuses their brain they will say, 'What the hell's taking so long?' And knowing what the answer is doesn't help them at all. One thing I've read about you consistently, though, is you are known for working quite quickly when you do setups. Whereas a lot of DPs will literally spend hours and hours and hours lighting a scene before it's shot, and you have a reputation for working very quickly, getting all the lights set up, and then you just do it. Well, I'm glad for that reputation. Is it deserved? Or do you disagree with it? I have no way of knowing, and I don't think it's necessarily -- it's not something whether you know what to do and then you do it quickly. It's not that precise a condition. Because there isn't any right way or wrong way to do anything semi-artful. It is when they work out a schedule, when they go to the quantification of the making of the film. Somebody somewhere has to factor in, 'Is he a fast worker? Can he work with less equipment? How does he relate to this actor?' All these personal issues, when they try to budget a film and see what elements are involved in a film, somebody on some level, sometimes not necessarily intelligently, but they are obliged to quantify it: What will it cost? What will it make? How much can we do with this actor with this kind of story released at this time of the year when such-and-such a mood is in the country, or whether we must get the teenagers -- all those things, by the nature of our system, even though some may think it's making art or telling the story and so forth, the basic story is, what are we selling, and how's best to sell it? And that goes for directors of photography. It goes, and sometimes it goes well. I mean, on working with Billy Crystal on “61*,” which was a film for television, for HBO.

Thomas Jane and Billy Crystal on the set of "61*." I love that film. Terrific film. I'm glad you like it, because it's important for you to know or anybody to know, that the spirit on the film, the attitude of the people, the knowledge of the director, the communication, the making of it, can affect the quality of the film -- if you want to call it, the entertainment value. And also the personality. Billy is just a really good man. As a director he knew baseball, he knew the players, he knew the story. He was very respectful to me, because I'm an older person in a time when you're shooting something which required a lot of physical running around with a very tight schedule, so, I mean, it's an example of a group of people who worked well together, and the crew felt the same way. And that happens on some pictures. It even happened when I worked on “Big Love.” There's a good spirit amongst the actors and the crew, a family aspect so that no matter how good the show is or not, the social experience is very important to the people's life, because they spend so much of their life at work. Getting back to some of the men portrayed in Something's Gonna Live, you know, the one thing, the undercurrent, the subtext in the film that really struck me, especially when Bob Boyle and the other gentleman who worked on The Birds with him went back to Bodega Bay -- his name is escaping me at the moment -- was ageism, that exists in the film business. Bob Boyle continued to work well into his eighties, then of course he was an instructor at AFI, but the other gentleman, he hadn't worked in years, and really the way Henry Bumstead and Conrad Hall kept working is they each had a director that just saw what jewels they were: Clint Eastwood with Henry Bumstead, and of course Sam Mendes with Conrad Hall. And it just made me wonder, if it weren't for these guys, who are very smart guys, who recognize what unique talents they were, I wonder if people would not hire them simply because they weren't young anymore, even though that has nothing to do with the amount of talent they bring to the table. Yeah, that could go into it. I mean, it's hard to, yeah, ageism is part of it. Insurance companies, for example, when you take cameramen. I forget what feature I shot fairly late in my life, it wasn't a John Sayles film, it was something else. Cameramen get physicals before, just for the insurance company, and I'm really in terrific shape. Obviously. But the lady at the insurance company said that they would like to know, if I couldn't complete the film, who I would like to replace me -- which, first I couldn't quite understand what that meant, but then I thanked her, because she was not obliged to say that to me, or even to think that, because they wouldn't think about a person who was in their seventies -- I guess I was in my seventies then. So I thought, so then I figured out what that meant, so I said, 'Well, I'd like Conrad Hall,' who was fairly old at that time (laughs), so the insurance companies do it, and I'm sure they do that with actors. Of course, with art directors I really don't know. Certainly the Japanese art director, since he was blind, you could hardly call that ageism. You could attribute his time at Manzanar (WW II Japanese-American internment camp) as a cause of diminishing his health, but he said it just connected him to good people in Chicago. It was a good example of a guy taking a bad situation and finding what was good about it, and having him bring that forward. That's what came out in the film to me: All of you guys had such incredible attitudes. You're eighty-eight, is that correct? Yeah. Yeah. Do you see a correlation between a positive attitude and health? I think being ornery helps a lot. I mean, I use the word "ornery" or crotchety or something like that. Older people being passionate, you know, passion you connect with the angle of the penis or something (laughs), but the older people, just "ornery" and stubborn, are dedicated enough to say, 'I'm not ready to go, I've got something -- Something's Gonna Live' -- and I think that it's true, that the guys in the film had that feeling, and they weren't, they didn't play the ageism thing, at least in the film, and I don't think they really did in life. I think that they looked back at their lives, and they looked back at the good things that they got, not just out of themselves, but out of their friends and even some aspects of the studio being sensitive to them. Which, employers now, by the nature of the business, are less able to show it. Personally, yes, but people in leadership positions in the entertainment now, are under pressure. Well, you talked about that with Sam Mendes, when Sam Mendes said nowadays, unlike back in the golden age of Hollywood, when the studios were run by guys who were, in their own way, they were real bastards, but they were filmmakers first and foremost, they weren't heads of major corporations like GE, and when you've got a company like GE whose primary source of income is defense contracting, you know, they have a very different agenda than someone like Jack Warner, who just wanted to make movies.The whole consolidation of communication. You know, Conrad, when he was talking about being an artist, he talked about, we were communicators. We don't wanna just do our work and then put it in our closet somewhere. We wanna communicate. And so what we communicate becomes important to us, and that doesn't mean every film you make has to drive people to the barricades, but it should explore the human condition, even about In Cold Blood -- in the film they gave examples of In Cold Blood -- does that mean Conrad was in favor of the guy who killed people? Or, I'm thinking, I'm thinking about Sean Penn in the film about the guy on death row… Dead Man Walking? Dead Man Walking. I'm thinking about Sean Penn in Dead Man Walking, when he's about to be executed, and they asked him, 'What are the last words, what did you have to say?' and he said, 'Well, killing is bad, whether I do it, y'all do it, or the government does it.' And that's what -- today I looked at the TV, and I'm looking at 9/11, and hearing about the sacred ground of the World Trade Center, and wondering what, why is it sacred? Because these mostly Saudi Arabian fanatics who ran airplanes into a center of Capitalism in New York, and also into the Pentagon, the center of militarism, of worldwide militarism in the world, and also in an attempt to destroy buildings in Washington, D.C. -- what makes those locations sacred is a perversion of what the word “sacred” is. What you have here is a crime against people. The people in those buildings who were murdered. And what can be celebrated are the brave firemen and those people who tried to save human lives, so that's what 9/11 is. 9/11 is not for revenge. It's not for revenge, as it's been used. Now what does that have to do with us talking about movies? We have now Life: The Movie. Life: The Movie, with the words, with the images, with the teleprompters, with the control of feelings, because facts -- facts, per se -- are sprinkled in. But they're not facts, they're facts that are taken by polls, someone gives percentages of this and that. And so when they say, 'Most of the people think that they should not build this big building that'll have a mosque in within three blocks of this sacred place,' then this is supposed to be an example of democracy by taking a poll the way an advertising agency will decide who will buy what, or how well the system is presenting this movie, this story on TV and on discussions and so forth. So I would like to make a movie from looking at the teleprompters, from sitting in the conference room, as I have on -- I made many cigarette commercials, beer commercials, so I've sat with advertising agency guys, where they have psychologists, where they have test people come in, where they put electrodes on them, and they even have a place here – a preview -- and they discuss 'We can't have that actor, no, his stomach is a little big, we don't want any fat guys in a beer commercial.” So I'm saying: Life: The Movie, because they've gotten us into fiction. And fiction can erase logic. Even The Hurt Locker. The Hurt Locker, when the military first saw that film, they hated it. They thought it was anti-military. And they then had the advisors -- I don't know if you know this -- they had advisors on the film who were contractors and who knew the language and who helped the scriptwriter have the dialogue accurate. Well, they then had a lawsuit against the film to try to keep the film from coming out, and can say they said they were the legitimate writers of the film. And then it was necessary -- what's the lady director's name? Kathryn Bigelow Yeah, Kathryn Bigelow, when she received the (Oscar), she thanked the firemen, she thanked the policemen, she thanked the U.S. military, she made every effort to make sure that it was clear that she did not consider this film -- my view of it was not: something which was counter, which they call 'controversial' -- that's another one of those words, is that anything which is against prevalent or status-quo viewpoint I think is called 'controversial,' meaning, elevating the word 'controversy' into -- so I don't know how I got on this subject, you can cut this interview, but the basic point I'm trying to say is that we have to know that we're being conditioned. We have been over some time conditioned to accept Life: The Movie. Life: The TV Show. Life: The Personal Interactions. Because of a lot of reasons. One of them is just simple space and time. You know: Get to the point. Right. Get to the point. Because at some point there's gotta be the commercial. At some point there's gotta be the payoff. At some point there has to be the element of excitement, because somehow we feel: Keep moving and keep accelerating -- that that in itself is progress. When some contemplation or some examination or some interplay back and forth -- even to understand what makes a person a person who thinks they're a very good Christian, wanted to go say, 'We should kill somebody.' You know? Not to just say that they're crazy, but to have the time to interact with them, or have me interact, to see where they are, because I believe. I think Chris Hedges, for example, speaks very well on this subject, to go beyond the stories that surround us and that divide us, and to go back to the humanity. And that's why I think films or ideas that deal with the environment, and certain things which are overtly human on the planet can allow us to look back at those other things, that say, look at -- to be able to look at all of us the way the astronauts looked at (us), or if some people are religious, the way god looks at us, not just as people sitting here in L.A., but including animals, including all living things. Including what's under the earth, the oil, the water. (laughs) Yeah. And this is exactly what Medium Cool is about. This is something that has been on your mind for a long time. Studs Turkel was my very good friend, from high school days. In fact, I acted in the theater that Studs had, the Chicago rep group, so Studs was one who knew theater and knew drama, and also knew people. And he was sort of like, his views and things were part of Howard Zinn's thing. He was a very progressive thinker. Well, he played a very important role in that film. He's credited as "Our Man in Chicago" in the opening credits. Yeah, well, he helped me pick the cast. He introduced me to Peggy Terry. There are whole sections that are not in the film, of the workers' group organizing at Motorola. Verna Bloom, the actress in it, I have shots of her working at Motorola and in front of TV sets. The scene with the black militants always felt very real to me, even though I know they were all actors. I do remember the black militant scene, where the guy says, 'Yeah,' somebody shoots Mr. Charlie,’ he says, 'and then they look into you, they know your family, they know the cops are comin' after you with…’ (laughs as actual sirens blare outside). You get through the idea, is that, that people, people are social. Human beings are social beings. And total anonymity -- and that can mean just being neglected by family, or interrelations, and so forth, is a hardship. And one of the ways that breaks anonymity is to be certified as existing. In our present culture, being on TV is a certification that you are somebody. Jesse Jackson, you know. (laughs) Now you may be somebody because you -- didn't matter what the hell you did. Even if you left your kid locked in, closed in the car on a hot day, you forgot to roll the window down, you know, or whatever. If you are an actor and you got bunk, you know: 'As long as they spell my name right.' But just even ordinary people who know that nobody knows anything, so television makes you somebody. And that's it, that's it -- if you can do something to get their attention. This is the way advertising functions. You look at ads, a lot of times you don't know what the hell they're selling. Because the first thing they have to do is have to get your attention. And in personal life, all of us at some point, we need attention. And you cannot just say selfish attention -- it can be just human interaction. And hopefully that human interaction can be not just personally useful, but socially useful. And unfortunately a lot of it gets diverted into being somebody, being quantifiable, besides being visible, also to have power, you can have money. And of course being visible is the way also to get money, and having money has to do with control of people. So all those quantifiable things which are culturally built in, which we'd call, 'She's very successful' -- you'd have no way of knowing she's very successful, except to know that somebody is paying her something that makes her happy. What I hear you talking about, are varying degrees of propaganda. And over the past thirty and forty years, how propaganda, the line between propaganda and legitimate news and legitimate storytelling, and advertising, and all these elements have become hopelessly blurred. It's like they're all in one big soup, and we're now just constantly being bombarded with that soup. It's the unanimity of the bombardment, and there's always been a bombardment, there's always been people trying to sell you something, and arguments, but there's always been more variety. Growing up in Chicago, just the newspapers, there were four newspapers. There were four newspapers. And they were somewhat different. Radio stations, you would hear the news on different radio stations, and you would hear different news. You know? They were different, they even have WCFL, they had the Voice of Labor radio station. WGN would be the Tribune station. They had different things. And the commentators would be different. You know? They would be different people, different personalities. None of them, like, revolutionary. But you did feel that there was a variety of choice, and what's more, the system knows that this big conflict -- the Republican or Democrat -- is really a false dilemma. In speechmaking, when they teach public speaking, they say the thing to do to make a convincing argument is to create a false dilemma. If you don't believe in this, then you have to believe in that. Your choices, the areas of your choice are within this frame. And when they set the frame, then they've got you coming and going. Obama can go out and do exactly what the Republicans are doing, for just a big example. And they're obliged to say something different, otherwise, if we're really as in-tune on certain basic things, they're doing the same things, some with better rhetoric, some with more nuance. Now that's not just -- how is it different in the '60s, it was somewhat different, the '60s were transition point where the system got noticeably slicker. They weren't gonna go beat kids in the street, they wouldn't hit newspeople, they would, the whole getting rid of the Viet Nam syndrome, figuring out how to control the media. All those things are to how the story comes to people. We want to make a film now with any military equipment, of any kind, you have, you can have millions, you can have millions of dollars of equipment, personnel, help, the script has to be, has to be okayed, every possible way. It's like the '50s all over again, really. It's almost like the '60s never happened. Yeah, except that the voice, the stories, that you get through the conventional ways, are almost unanimous. If you ask anybody: 'What is a terrorist?' You know? You ask anybody: 'What do you mean by "Security"?' 'What do you mean about the economy doing better?' Just definitions, we're talking about, because once they establish their shorthand, you know, then you listen to NPR, and the guy's voice goes up: 'Well, the stock market was firm today. It might even go up a point or so.' What the fuck does that mean to me? Huh? What does it mean? Why should it mean? Huh? But those questions are not being asked. And they're asking, to talk about Afghanistan or big things, the questions are not being asked. Now, the people talk about the Internet, you know? One of the ways to demobilize people is to have too much shit. Now I'm not saying that they shouldn't, I'm very much in favor of Internet neutrality, but this is, when you see these government agencies that get challenged about certain things, how they answer the challenge is they say, 'We're working on it,' and then they will have something which is 2,000 pages long, with all kinds of obscure or specialized language -- that's the other way that they protect -- so nobody's gonna say 'They didn't--' or, 'Your agency is there to protect the people from the natural avarice of corporate greed. They're there to protect the oversee, the banks, you're there to oversee the drugs, you're there to oversee the chemicals that are in our food, or the medicines that we need, or the gas, the gas that goes into our homes.' We had an explosion here the other day. Or when people that call in and say they've been smelling gas for two weeks, and so forth, nothing's been done, well -- those agencies are populated by good people. But their priorities are to be efficient, which means to give less and get more. And, and that can't be challenged seriously by the storytelling. And trying to get back to what you wanted to talk about, film, I'm saying that: Who tells the story, and how they tell the story, is vital to democracy and to the intelligence of the people. And when intelligence of the people get diverted to, to, to tribalism, to us and them, to divisions, to diversions. From the real enemy -- and the real enemy is the misdirection of our culture, or societal priorities -- are we here on this planet to live together, to work together, to be part of Mother Earth, is it here, are we here ready to work? Ready to know one another? To respect one another? Or are we here to compete and to control and to dominate, and to take? And when -- and this just didn't happen with Bush and Clinton and the rest -- this has happened incrementally, and along the way there have been a lot of good things happened, but now we have to say the good things. We have to identify what the good things are. Certainly basic things of food and clothing, health, not spending our resources on killing and on the domination. And see, like in films, again, talking about films, see how many films try to equate World War II with 'the good war,' with what's going on now. You see the idealization today with our troops, you wouldn't want to hurt our troops. Burning the Koran would hurt our troops. Now, those images, those images are not identifiable if you close your eyes and say, 'Let me look at our guys in Afghanistan. What are they doing? Or in Iraq.' You know? Betray us, it'll hurt our troops.

Thomas Jane and Billy Crystal on the set of "61*." I love that film. Terrific film. I'm glad you like it, because it's important for you to know or anybody to know, that the spirit on the film, the attitude of the people, the knowledge of the director, the communication, the making of it, can affect the quality of the film -- if you want to call it, the entertainment value. And also the personality. Billy is just a really good man. As a director he knew baseball, he knew the players, he knew the story. He was very respectful to me, because I'm an older person in a time when you're shooting something which required a lot of physical running around with a very tight schedule, so, I mean, it's an example of a group of people who worked well together, and the crew felt the same way. And that happens on some pictures. It even happened when I worked on “Big Love.” There's a good spirit amongst the actors and the crew, a family aspect so that no matter how good the show is or not, the social experience is very important to the people's life, because they spend so much of their life at work. Getting back to some of the men portrayed in Something's Gonna Live, you know, the one thing, the undercurrent, the subtext in the film that really struck me, especially when Bob Boyle and the other gentleman who worked on The Birds with him went back to Bodega Bay -- his name is escaping me at the moment -- was ageism, that exists in the film business. Bob Boyle continued to work well into his eighties, then of course he was an instructor at AFI, but the other gentleman, he hadn't worked in years, and really the way Henry Bumstead and Conrad Hall kept working is they each had a director that just saw what jewels they were: Clint Eastwood with Henry Bumstead, and of course Sam Mendes with Conrad Hall. And it just made me wonder, if it weren't for these guys, who are very smart guys, who recognize what unique talents they were, I wonder if people would not hire them simply because they weren't young anymore, even though that has nothing to do with the amount of talent they bring to the table. Yeah, that could go into it. I mean, it's hard to, yeah, ageism is part of it. Insurance companies, for example, when you take cameramen. I forget what feature I shot fairly late in my life, it wasn't a John Sayles film, it was something else. Cameramen get physicals before, just for the insurance company, and I'm really in terrific shape. Obviously. But the lady at the insurance company said that they would like to know, if I couldn't complete the film, who I would like to replace me -- which, first I couldn't quite understand what that meant, but then I thanked her, because she was not obliged to say that to me, or even to think that, because they wouldn't think about a person who was in their seventies -- I guess I was in my seventies then. So I thought, so then I figured out what that meant, so I said, 'Well, I'd like Conrad Hall,' who was fairly old at that time (laughs), so the insurance companies do it, and I'm sure they do that with actors. Of course, with art directors I really don't know. Certainly the Japanese art director, since he was blind, you could hardly call that ageism. You could attribute his time at Manzanar (WW II Japanese-American internment camp) as a cause of diminishing his health, but he said it just connected him to good people in Chicago. It was a good example of a guy taking a bad situation and finding what was good about it, and having him bring that forward. That's what came out in the film to me: All of you guys had such incredible attitudes. You're eighty-eight, is that correct? Yeah. Yeah. Do you see a correlation between a positive attitude and health? I think being ornery helps a lot. I mean, I use the word "ornery" or crotchety or something like that. Older people being passionate, you know, passion you connect with the angle of the penis or something (laughs), but the older people, just "ornery" and stubborn, are dedicated enough to say, 'I'm not ready to go, I've got something -- Something's Gonna Live' -- and I think that it's true, that the guys in the film had that feeling, and they weren't, they didn't play the ageism thing, at least in the film, and I don't think they really did in life. I think that they looked back at their lives, and they looked back at the good things that they got, not just out of themselves, but out of their friends and even some aspects of the studio being sensitive to them. Which, employers now, by the nature of the business, are less able to show it. Personally, yes, but people in leadership positions in the entertainment now, are under pressure. Well, you talked about that with Sam Mendes, when Sam Mendes said nowadays, unlike back in the golden age of Hollywood, when the studios were run by guys who were, in their own way, they were real bastards, but they were filmmakers first and foremost, they weren't heads of major corporations like GE, and when you've got a company like GE whose primary source of income is defense contracting, you know, they have a very different agenda than someone like Jack Warner, who just wanted to make movies.The whole consolidation of communication. You know, Conrad, when he was talking about being an artist, he talked about, we were communicators. We don't wanna just do our work and then put it in our closet somewhere. We wanna communicate. And so what we communicate becomes important to us, and that doesn't mean every film you make has to drive people to the barricades, but it should explore the human condition, even about In Cold Blood -- in the film they gave examples of In Cold Blood -- does that mean Conrad was in favor of the guy who killed people? Or, I'm thinking, I'm thinking about Sean Penn in the film about the guy on death row… Dead Man Walking? Dead Man Walking. I'm thinking about Sean Penn in Dead Man Walking, when he's about to be executed, and they asked him, 'What are the last words, what did you have to say?' and he said, 'Well, killing is bad, whether I do it, y'all do it, or the government does it.' And that's what -- today I looked at the TV, and I'm looking at 9/11, and hearing about the sacred ground of the World Trade Center, and wondering what, why is it sacred? Because these mostly Saudi Arabian fanatics who ran airplanes into a center of Capitalism in New York, and also into the Pentagon, the center of militarism, of worldwide militarism in the world, and also in an attempt to destroy buildings in Washington, D.C. -- what makes those locations sacred is a perversion of what the word “sacred” is. What you have here is a crime against people. The people in those buildings who were murdered. And what can be celebrated are the brave firemen and those people who tried to save human lives, so that's what 9/11 is. 9/11 is not for revenge. It's not for revenge, as it's been used. Now what does that have to do with us talking about movies? We have now Life: The Movie. Life: The Movie, with the words, with the images, with the teleprompters, with the control of feelings, because facts -- facts, per se -- are sprinkled in. But they're not facts, they're facts that are taken by polls, someone gives percentages of this and that. And so when they say, 'Most of the people think that they should not build this big building that'll have a mosque in within three blocks of this sacred place,' then this is supposed to be an example of democracy by taking a poll the way an advertising agency will decide who will buy what, or how well the system is presenting this movie, this story on TV and on discussions and so forth. So I would like to make a movie from looking at the teleprompters, from sitting in the conference room, as I have on -- I made many cigarette commercials, beer commercials, so I've sat with advertising agency guys, where they have psychologists, where they have test people come in, where they put electrodes on them, and they even have a place here – a preview -- and they discuss 'We can't have that actor, no, his stomach is a little big, we don't want any fat guys in a beer commercial.” So I'm saying: Life: The Movie, because they've gotten us into fiction. And fiction can erase logic. Even The Hurt Locker. The Hurt Locker, when the military first saw that film, they hated it. They thought it was anti-military. And they then had the advisors -- I don't know if you know this -- they had advisors on the film who were contractors and who knew the language and who helped the scriptwriter have the dialogue accurate. Well, they then had a lawsuit against the film to try to keep the film from coming out, and can say they said they were the legitimate writers of the film. And then it was necessary -- what's the lady director's name? Kathryn Bigelow Yeah, Kathryn Bigelow, when she received the (Oscar), she thanked the firemen, she thanked the policemen, she thanked the U.S. military, she made every effort to make sure that it was clear that she did not consider this film -- my view of it was not: something which was counter, which they call 'controversial' -- that's another one of those words, is that anything which is against prevalent or status-quo viewpoint I think is called 'controversial,' meaning, elevating the word 'controversy' into -- so I don't know how I got on this subject, you can cut this interview, but the basic point I'm trying to say is that we have to know that we're being conditioned. We have been over some time conditioned to accept Life: The Movie. Life: The TV Show. Life: The Personal Interactions. Because of a lot of reasons. One of them is just simple space and time. You know: Get to the point. Right. Get to the point. Because at some point there's gotta be the commercial. At some point there's gotta be the payoff. At some point there has to be the element of excitement, because somehow we feel: Keep moving and keep accelerating -- that that in itself is progress. When some contemplation or some examination or some interplay back and forth -- even to understand what makes a person a person who thinks they're a very good Christian, wanted to go say, 'We should kill somebody.' You know? Not to just say that they're crazy, but to have the time to interact with them, or have me interact, to see where they are, because I believe. I think Chris Hedges, for example, speaks very well on this subject, to go beyond the stories that surround us and that divide us, and to go back to the humanity. And that's why I think films or ideas that deal with the environment, and certain things which are overtly human on the planet can allow us to look back at those other things, that say, look at -- to be able to look at all of us the way the astronauts looked at (us), or if some people are religious, the way god looks at us, not just as people sitting here in L.A., but including animals, including all living things. Including what's under the earth, the oil, the water. (laughs) Yeah. And this is exactly what Medium Cool is about. This is something that has been on your mind for a long time. Studs Turkel was my very good friend, from high school days. In fact, I acted in the theater that Studs had, the Chicago rep group, so Studs was one who knew theater and knew drama, and also knew people. And he was sort of like, his views and things were part of Howard Zinn's thing. He was a very progressive thinker. Well, he played a very important role in that film. He's credited as "Our Man in Chicago" in the opening credits. Yeah, well, he helped me pick the cast. He introduced me to Peggy Terry. There are whole sections that are not in the film, of the workers' group organizing at Motorola. Verna Bloom, the actress in it, I have shots of her working at Motorola and in front of TV sets. The scene with the black militants always felt very real to me, even though I know they were all actors. I do remember the black militant scene, where the guy says, 'Yeah,' somebody shoots Mr. Charlie,’ he says, 'and then they look into you, they know your family, they know the cops are comin' after you with…’ (laughs as actual sirens blare outside). You get through the idea, is that, that people, people are social. Human beings are social beings. And total anonymity -- and that can mean just being neglected by family, or interrelations, and so forth, is a hardship. And one of the ways that breaks anonymity is to be certified as existing. In our present culture, being on TV is a certification that you are somebody. Jesse Jackson, you know. (laughs) Now you may be somebody because you -- didn't matter what the hell you did. Even if you left your kid locked in, closed in the car on a hot day, you forgot to roll the window down, you know, or whatever. If you are an actor and you got bunk, you know: 'As long as they spell my name right.' But just even ordinary people who know that nobody knows anything, so television makes you somebody. And that's it, that's it -- if you can do something to get their attention. This is the way advertising functions. You look at ads, a lot of times you don't know what the hell they're selling. Because the first thing they have to do is have to get your attention. And in personal life, all of us at some point, we need attention. And you cannot just say selfish attention -- it can be just human interaction. And hopefully that human interaction can be not just personally useful, but socially useful. And unfortunately a lot of it gets diverted into being somebody, being quantifiable, besides being visible, also to have power, you can have money. And of course being visible is the way also to get money, and having money has to do with control of people. So all those quantifiable things which are culturally built in, which we'd call, 'She's very successful' -- you'd have no way of knowing she's very successful, except to know that somebody is paying her something that makes her happy. What I hear you talking about, are varying degrees of propaganda. And over the past thirty and forty years, how propaganda, the line between propaganda and legitimate news and legitimate storytelling, and advertising, and all these elements have become hopelessly blurred. It's like they're all in one big soup, and we're now just constantly being bombarded with that soup. It's the unanimity of the bombardment, and there's always been a bombardment, there's always been people trying to sell you something, and arguments, but there's always been more variety. Growing up in Chicago, just the newspapers, there were four newspapers. There were four newspapers. And they were somewhat different. Radio stations, you would hear the news on different radio stations, and you would hear different news. You know? They were different, they even have WCFL, they had the Voice of Labor radio station. WGN would be the Tribune station. They had different things. And the commentators would be different. You know? They would be different people, different personalities. None of them, like, revolutionary. But you did feel that there was a variety of choice, and what's more, the system knows that this big conflict -- the Republican or Democrat -- is really a false dilemma. In speechmaking, when they teach public speaking, they say the thing to do to make a convincing argument is to create a false dilemma. If you don't believe in this, then you have to believe in that. Your choices, the areas of your choice are within this frame. And when they set the frame, then they've got you coming and going. Obama can go out and do exactly what the Republicans are doing, for just a big example. And they're obliged to say something different, otherwise, if we're really as in-tune on certain basic things, they're doing the same things, some with better rhetoric, some with more nuance. Now that's not just -- how is it different in the '60s, it was somewhat different, the '60s were transition point where the system got noticeably slicker. They weren't gonna go beat kids in the street, they wouldn't hit newspeople, they would, the whole getting rid of the Viet Nam syndrome, figuring out how to control the media. All those things are to how the story comes to people. We want to make a film now with any military equipment, of any kind, you have, you can have millions, you can have millions of dollars of equipment, personnel, help, the script has to be, has to be okayed, every possible way. It's like the '50s all over again, really. It's almost like the '60s never happened. Yeah, except that the voice, the stories, that you get through the conventional ways, are almost unanimous. If you ask anybody: 'What is a terrorist?' You know? You ask anybody: 'What do you mean by "Security"?' 'What do you mean about the economy doing better?' Just definitions, we're talking about, because once they establish their shorthand, you know, then you listen to NPR, and the guy's voice goes up: 'Well, the stock market was firm today. It might even go up a point or so.' What the fuck does that mean to me? Huh? What does it mean? Why should it mean? Huh? But those questions are not being asked. And they're asking, to talk about Afghanistan or big things, the questions are not being asked. Now, the people talk about the Internet, you know? One of the ways to demobilize people is to have too much shit. Now I'm not saying that they shouldn't, I'm very much in favor of Internet neutrality, but this is, when you see these government agencies that get challenged about certain things, how they answer the challenge is they say, 'We're working on it,' and then they will have something which is 2,000 pages long, with all kinds of obscure or specialized language -- that's the other way that they protect -- so nobody's gonna say 'They didn't--' or, 'Your agency is there to protect the people from the natural avarice of corporate greed. They're there to protect the oversee, the banks, you're there to oversee the drugs, you're there to oversee the chemicals that are in our food, or the medicines that we need, or the gas, the gas that goes into our homes.' We had an explosion here the other day. Or when people that call in and say they've been smelling gas for two weeks, and so forth, nothing's been done, well -- those agencies are populated by good people. But their priorities are to be efficient, which means to give less and get more. And, and that can't be challenged seriously by the storytelling. And trying to get back to what you wanted to talk about, film, I'm saying that: Who tells the story, and how they tell the story, is vital to democracy and to the intelligence of the people. And when intelligence of the people get diverted to, to, to tribalism, to us and them, to divisions, to diversions. From the real enemy -- and the real enemy is the misdirection of our culture, or societal priorities -- are we here on this planet to live together, to work together, to be part of Mother Earth, is it here, are we here ready to work? Ready to know one another? To respect one another? Or are we here to compete and to control and to dominate, and to take? And when -- and this just didn't happen with Bush and Clinton and the rest -- this has happened incrementally, and along the way there have been a lot of good things happened, but now we have to say the good things. We have to identify what the good things are. Certainly basic things of food and clothing, health, not spending our resources on killing and on the domination. And see, like in films, again, talking about films, see how many films try to equate World War II with 'the good war,' with what's going on now. You see the idealization today with our troops, you wouldn't want to hurt our troops. Burning the Koran would hurt our troops. Now, those images, those images are not identifiable if you close your eyes and say, 'Let me look at our guys in Afghanistan. What are they doing? Or in Iraq.' You know? Betray us, it'll hurt our troops.  Wexler poses before the "wall of fame" in his Santa Monica home. Right. But, again, that's very simple propaganda. But we buy it, because we can't go in -- we can't say, what the hell, we're spending over half of the resources of the people of America who can't afford health care, can't send their kids to school, have to fire teachers, have people unemployed -- to give a three-billion-dollar loan to the bank of Afghanistan last week. Or to build nuclear submarines, to roam the world with missiles which would be the end of the world in a lot of ways, if launched, one way or another. Now, no one says -- no one says that stuff. Except crazy guys like me. But don't you think the reason that's the case is because, as we've been talking about, we're being bombarded by all this stuff, and we created several generations who've become -- instead of being interested in being informed, instead of gathering knowledge, we've become addicted to sensation. And when you're addicted to sensation, you lack intellectual stimulation as your brain develops, when you're growing up. And because of that you lack the ability to process complex information, and see subtext in things, and to see subtleties in things, and as a result you have a whole group of people -- that's the reason why we're becoming dumber as a nation. When you have a whole group of people who only understand buzzwords. In other words, all these people in the Tea Party, if you give them a statement that uses the words 'Jesus Christ' and 'white people' and 'the economy' with the subtext of hate and fear, they're gonna buy into it. Well, what you say is true. And it's not something we can change overnight, because it has been incremental. And all of us, all of us, a part of it, you know? We've grown up with things, I mean, you know, in Who Needs Sleep?, I begin, I'm in my red El Camino, and I really loved that car. But it's a thing. (laughs) Now, I mean I grew up with wanting things, and buying things, and having things, and so forth. And what we think -- needing that and having that represent me and so forth is something that, which is part of what made us great, what made us have a better life. What made people from Europe or from other places have an opportunity, thinking they can come here, and have a chance to move out of a class, a heavily, heavily delineated class system. But in general what you say is true. But, one of the reasons what you'd call propaganda works is, when it works, it works. (laughs) Yeah. It's effective. It's one of the reasons the Nazis gained power so quickly, because they were master propagandists, and they tapped into the fear, and the anger, that gripped the German people, post-World War I. And that's why Hitler gained power so quickly. Yeah. They were better propagandists even than they were soldiers, and they were damn good soldiers. Howard Zinn was probably the best at that, the only example I know, of someone who can give you a taste of how we have been brought up with a certain aspect of our history which is not necessarily the primary aspect of our history. Yeah. I was just thinking, my brother and I went to the Parkway Theater in Chicago, every day, to see Cowboys-and-Indian movies. We loved, we'd see the cowboys, you know, shooting down Indian, and they'd fall off the horse -- whoo-ahh! -- and we would cheer. We were brought up in thinking, even when we think today about the Wild West and so forth, we never think of us as coming and killing and poisoning and a kind of genocide against the 'savages' that were there. Even Howard Zinn, beginning with his Columbus diaries about -- now, I'm not saying that we have to say, beat our chests and say, 'Oh, god, we're terrible Americans, always been terrible,' and so forth, but I think it's important to know our history, and if you know your history then you try to build on the good parts of it. Particularly now when things are more critical then ever I think, certainly in my lifetime. In totality, when they talk about the planet, they also talk about the rebellion that is brewing all over the world, just on the basis of food, water, not to mention devastations of war, you know, rape, killing, child malnutrition, all disease, all those things are trying -- have minor forms of rebellion, and the establishment is also developing all kinds of ways of avoiding its awareness and also how to surpress -- I know in Medium Cool, I studied a book about crowd control that they had, and I read this a month or two before the demonstrations in Chicago. Before I wrote the script, actually. And one of the things that they had for the police was a gas that they could shoot at demonstrators that would cause them to shit. And the book had an asterisk on that, because they're looking for non-lethal crowd control. It said: 'May not use because of directional -- possibilities of directional problems' -- which meant that if the cops shot it, the cops might be shitting. And so one of my early scripts for Medium Cool, I had this scene where the cops were controlling crowds and they were shitting (laughs) -- but it's, when you were talking about Medium Cool, the script was written basically a month before, a month and a half before the convention. Right. And registered at the Writer's Guild and everything. A lot of people referred to Medium Cool as a documentary. Well, it was in a way. One thing I found fascinating which was touched on in Something's Gonna Live, which I didn't know, was that you actually scripted the riot scenes, anticipating what was gonna happen there. Oh, is that in Something's Gonna Live? Yeah. I always thought you just were going to shoot Robert Forster and Verna Bloom at the convention, and then the riots happened around you, so you just were there, and shot it. No. It was true cinema verité. No, the script, which I have in the handwriting, it's in the office there, I did anticipate. I knew there was going to be (trouble), if the Democratic party did not respond to the anti-war movement, which they didn't, I knew that there were planned demonstrations, and I knew that there would probably be some confrontations. And I knew Abbie Hoffman, I knew Tom Hayden and some of the other people, and they had some plans for theater, a lot of crazy stuff, nothing violent, but I knew that the cops would probably, you know, make it difficult for 'em. I had no idea of the scope of the repression. When you actually found yourself in the middle of that, what was labeled a police riot, were you scared? I know you got hit with a tear-gas canister, that's the most infamous scene in the movie: 'Look out, Haskell, it's real!' (laughs) (laughs) Well, actually, in shooting, I was not scared, and I think one of the things that I felt, you know, looking through the camera, that I was looking at a movie, you know, that I'm somewhat impervious. I mean, I did, I was aware of Verna, for example. I would say, 'Verna--' We were blocked in the park, there was a scene, I said, 'Verna, just try to get out.' And so I figured the National Guard would stop her, but she started, so I photographed her, and she started to get out, and she got out, and one of the National Guard men, I don't know, might have looked down the front of her dress or something, but he turned around and let her out, so I was stuck in the park there, with my actress, outside. (laughs) I remember that scene. He kind of looks at her, because she had that bright yellow dress on, so you couldn't miss her, and just sort of lets her pass through. And actually he did say something to her, and in a voice-over, Verna Bloom was saying that she stayed in character, said, 'I'm looking for my little boy, my little boy is lost.' And he was like, 'Okay, go.' So there wasn't the drama that you were expecting there, but it was still effective, and it kind of, in a way, humanized the National Guardsman. Well, one of our guys in our crew was called up in the National Guard, and we saw him. And also, the National Guard training, which was a couple of weeks before the convention, three weeks before, my brother was a friend of that Army officer that talked about the National Guard, and this was a good example of theater-- I'm sorry, this was Jerry? Your brother Jerry? Yeah, Jerry. The National Guard training, you saw the guys acting like hippies, the other was, the mayor of the town, 'I'm here for you,' and all that, theater, filmmaking, you know? And then, the end of that, they yell, 'Let's get the guys with the camera,' and I don't know if you noticed, but they go to Forster's camera, and then they go to my camera, which was part of the whole story of the film, a lot of which is cut out, because the film has a number of times stolen somewhat an idea from Jean-Luc Godard where an actor goes to our camera, and the, when Forster goes to the head of the TV station, and he wants to shoot in the ghetto area, he says, 'Look, all they need is film.' And the studio head turns to my camera, and says, 'Look, they've got film,' and he goes back to the thing. And there are two or three things like that, at the roller games, but people then, I had showed it to some friends when I was cutting, and they didn't like that at all. In fact, they hated the ending. The one that's in there now, they hated it? Yeah. Oh, God. That's just one of the great endings in the history of movies. That's such a great ending. (laughs) Oh, please.

Wexler poses before the "wall of fame" in his Santa Monica home. Right. But, again, that's very simple propaganda. But we buy it, because we can't go in -- we can't say, what the hell, we're spending over half of the resources of the people of America who can't afford health care, can't send their kids to school, have to fire teachers, have people unemployed -- to give a three-billion-dollar loan to the bank of Afghanistan last week. Or to build nuclear submarines, to roam the world with missiles which would be the end of the world in a lot of ways, if launched, one way or another. Now, no one says -- no one says that stuff. Except crazy guys like me. But don't you think the reason that's the case is because, as we've been talking about, we're being bombarded by all this stuff, and we created several generations who've become -- instead of being interested in being informed, instead of gathering knowledge, we've become addicted to sensation. And when you're addicted to sensation, you lack intellectual stimulation as your brain develops, when you're growing up. And because of that you lack the ability to process complex information, and see subtext in things, and to see subtleties in things, and as a result you have a whole group of people -- that's the reason why we're becoming dumber as a nation. When you have a whole group of people who only understand buzzwords. In other words, all these people in the Tea Party, if you give them a statement that uses the words 'Jesus Christ' and 'white people' and 'the economy' with the subtext of hate and fear, they're gonna buy into it. Well, what you say is true. And it's not something we can change overnight, because it has been incremental. And all of us, all of us, a part of it, you know? We've grown up with things, I mean, you know, in Who Needs Sleep?, I begin, I'm in my red El Camino, and I really loved that car. But it's a thing. (laughs) Now, I mean I grew up with wanting things, and buying things, and having things, and so forth. And what we think -- needing that and having that represent me and so forth is something that, which is part of what made us great, what made us have a better life. What made people from Europe or from other places have an opportunity, thinking they can come here, and have a chance to move out of a class, a heavily, heavily delineated class system. But in general what you say is true. But, one of the reasons what you'd call propaganda works is, when it works, it works. (laughs) Yeah. It's effective. It's one of the reasons the Nazis gained power so quickly, because they were master propagandists, and they tapped into the fear, and the anger, that gripped the German people, post-World War I. And that's why Hitler gained power so quickly. Yeah. They were better propagandists even than they were soldiers, and they were damn good soldiers. Howard Zinn was probably the best at that, the only example I know, of someone who can give you a taste of how we have been brought up with a certain aspect of our history which is not necessarily the primary aspect of our history. Yeah. I was just thinking, my brother and I went to the Parkway Theater in Chicago, every day, to see Cowboys-and-Indian movies. We loved, we'd see the cowboys, you know, shooting down Indian, and they'd fall off the horse -- whoo-ahh! -- and we would cheer. We were brought up in thinking, even when we think today about the Wild West and so forth, we never think of us as coming and killing and poisoning and a kind of genocide against the 'savages' that were there. Even Howard Zinn, beginning with his Columbus diaries about -- now, I'm not saying that we have to say, beat our chests and say, 'Oh, god, we're terrible Americans, always been terrible,' and so forth, but I think it's important to know our history, and if you know your history then you try to build on the good parts of it. Particularly now when things are more critical then ever I think, certainly in my lifetime. In totality, when they talk about the planet, they also talk about the rebellion that is brewing all over the world, just on the basis of food, water, not to mention devastations of war, you know, rape, killing, child malnutrition, all disease, all those things are trying -- have minor forms of rebellion, and the establishment is also developing all kinds of ways of avoiding its awareness and also how to surpress -- I know in Medium Cool, I studied a book about crowd control that they had, and I read this a month or two before the demonstrations in Chicago. Before I wrote the script, actually. And one of the things that they had for the police was a gas that they could shoot at demonstrators that would cause them to shit. And the book had an asterisk on that, because they're looking for non-lethal crowd control. It said: 'May not use because of directional -- possibilities of directional problems' -- which meant that if the cops shot it, the cops might be shitting. And so one of my early scripts for Medium Cool, I had this scene where the cops were controlling crowds and they were shitting (laughs) -- but it's, when you were talking about Medium Cool, the script was written basically a month before, a month and a half before the convention. Right. And registered at the Writer's Guild and everything. A lot of people referred to Medium Cool as a documentary. Well, it was in a way. One thing I found fascinating which was touched on in Something's Gonna Live, which I didn't know, was that you actually scripted the riot scenes, anticipating what was gonna happen there. Oh, is that in Something's Gonna Live? Yeah. I always thought you just were going to shoot Robert Forster and Verna Bloom at the convention, and then the riots happened around you, so you just were there, and shot it. No. It was true cinema verité. No, the script, which I have in the handwriting, it's in the office there, I did anticipate. I knew there was going to be (trouble), if the Democratic party did not respond to the anti-war movement, which they didn't, I knew that there were planned demonstrations, and I knew that there would probably be some confrontations. And I knew Abbie Hoffman, I knew Tom Hayden and some of the other people, and they had some plans for theater, a lot of crazy stuff, nothing violent, but I knew that the cops would probably, you know, make it difficult for 'em. I had no idea of the scope of the repression. When you actually found yourself in the middle of that, what was labeled a police riot, were you scared? I know you got hit with a tear-gas canister, that's the most infamous scene in the movie: 'Look out, Haskell, it's real!' (laughs) (laughs) Well, actually, in shooting, I was not scared, and I think one of the things that I felt, you know, looking through the camera, that I was looking at a movie, you know, that I'm somewhat impervious. I mean, I did, I was aware of Verna, for example. I would say, 'Verna--' We were blocked in the park, there was a scene, I said, 'Verna, just try to get out.' And so I figured the National Guard would stop her, but she started, so I photographed her, and she started to get out, and she got out, and one of the National Guard men, I don't know, might have looked down the front of her dress or something, but he turned around and let her out, so I was stuck in the park there, with my actress, outside. (laughs) I remember that scene. He kind of looks at her, because she had that bright yellow dress on, so you couldn't miss her, and just sort of lets her pass through. And actually he did say something to her, and in a voice-over, Verna Bloom was saying that she stayed in character, said, 'I'm looking for my little boy, my little boy is lost.' And he was like, 'Okay, go.' So there wasn't the drama that you were expecting there, but it was still effective, and it kind of, in a way, humanized the National Guardsman. Well, one of our guys in our crew was called up in the National Guard, and we saw him. And also, the National Guard training, which was a couple of weeks before the convention, three weeks before, my brother was a friend of that Army officer that talked about the National Guard, and this was a good example of theater-- I'm sorry, this was Jerry? Your brother Jerry? Yeah, Jerry. The National Guard training, you saw the guys acting like hippies, the other was, the mayor of the town, 'I'm here for you,' and all that, theater, filmmaking, you know? And then, the end of that, they yell, 'Let's get the guys with the camera,' and I don't know if you noticed, but they go to Forster's camera, and then they go to my camera, which was part of the whole story of the film, a lot of which is cut out, because the film has a number of times stolen somewhat an idea from Jean-Luc Godard where an actor goes to our camera, and the, when Forster goes to the head of the TV station, and he wants to shoot in the ghetto area, he says, 'Look, all they need is film.' And the studio head turns to my camera, and says, 'Look, they've got film,' and he goes back to the thing. And there are two or three things like that, at the roller games, but people then, I had showed it to some friends when I was cutting, and they didn't like that at all. In fact, they hated the ending. The one that's in there now, they hated it? Yeah. Oh, God. That's just one of the great endings in the history of movies. That's such a great ending. (laughs) Oh, please.  The whole world is watching: Wexler in Medium Cool's iconic final shot. No. I get chills every time I see that ending. Well, it is pretty much what I'm talking about here. When I'm talking about fiction, and the stories, and so forth, that's exactly -- the last scene of the film, many's the filmmaker saying, 'Okay, my story is over. I'm gonna kill off my actors.' You know? And they kill 'em, she gets killed and he's gone, and the kid goes by in the car, a tourist, and he has a still camera, and takes a picture of the burning car. The camera pulls back, it's in the forest preserves of Chicago. It pulls back, and you see me shooting out toward the camera, you know the shot, turned to people. And the whole world's watching. Well, people didn't like that ending at all. They wanted their-- they'd say I’d chickened out, what's the end of the story? But the idea of, the idea of creating your truth, which is your fiction, even in our talking now, is a kind of fiction, it's not the dramatic right-(write)-down truth of language I'm using, the movement of my mouth, or what stories I recall, I am organizing material to communicate to you, and then, in turn, will then reorganize this lengthy bullshit into something coherent that coincides with your view, so that when (laughs), when it gets read by a beautiful young actress, she will then read that, and maybe appreciate what you've written, but then when she talks to her friends about it, or even when she thinks about it, it goes through her sensibility filter, which is as true as something, as solid as something that you could feel and touch, and that's why the ideas of democracy, I mean, cinema verité, truth and so forth, has to be colored with what is fiction. Yeah. You know, it seems that the consistent driving force in your life has been a strong social conscience. And some would argue that you come from an unlikely background to have such a conscience. What do you think gave birth to this conscience? Was there an inciting incident, or was it just the way you were hard-wired at birth? Well, you know, when you speak of my unlikely background, because my background, usually as written, is that I had a well-to-do family, and well-to-do families-- You grew up rich. Uh...yeah. Not growing up, we were relatively, six or seven years old, I think my dad sort of predicted the Depression, as a businessman, who was a graduated lawyer, my dad was in World War I, he didn't go overseas, but he was very much against World War I, he was a Eugene V. Debs Socialist, and the anti-war movement, anti-World-War movement was very strong. There were huge demonstrations in Washington. There was, even the comic strips had Little Orphan Annie, or her father is Daddy Warbucks, the whole idea of World War I overtly killing millions, millions in the world, for war profiteers, it was clear that it was not about any issues of the Huns and all the other things that were whipped up, 'Lafayette, we are here,' and all that stuff -- and beginnings of semi-Socialist ideology, was very strong, and particularly strong during the Depression. Did your dad maintain those ideals after he made his money? Those ideals were tempered, somewhat. Although he was active with Charlie Chaplin and millions of Americans for the opening of the second Front, which was a big deal. World War II, the U.S. was willing to stand by while 90% of the war was being fought with the Russians, hoping that they would bleed themselves white, and then finally they decided to invade the soft underbelly of Europe, as it was called. But no, as far as my parents, my mother worked, and I was born when she was very young, and she worked in her mother's bakery. And my family never, if my father was, like, rich, I never really knew that, you know? And his friends also were all these first-generation Jewish guys who had an element of social responsibility, coming from not-too-far from refugees from pogroms in Europe. Was your dad born overseas? No, he was born in Chicago. My mother, too. Where did their ancestors come from? Russia and Poland. It sounds like your dad was a tough guy. (pause) He was. I know he set you up with a studio, initially, after you got out of the service. And he called you a “magician,” right? (laughs) It's funny when things get printed. Yeah, I got a trust fund when I was twenty-one. It wasn't a lot of money, but it was pretty good. And my dad said, 'Now, what are you gonna do with life?' And I did work in Allied Radio in Stockholm, and I said, 'I don't know.' He said, 'You know, you should be a chemist.' And I said, 'What do you mean?' And he said, 'You're the only one I know who can take good money and turn it into shit.' (laughs) But then he was so happy when I got my first job as an assistant cameraman on the newsreels, and I brought home a check for $250, and I had been shooting little films of my own before that. Did he live to see you become a successful cameraman? I hadn't won any Academy Awards, no.